It makes me happy to know that this post will be the one knocking the “Covering Spaces” post off of the front page. This one will cover a related topic but (hopefully) with the noticable difference that while that post is trash, this one will be somewhat well-written. That being said, I’m going to be (mostly) stepping away from the (certain flavor of) number theory that I have been writing about, and make my next few posts more geometric/topological. 1 Kicking things off, this post will be about showing an equivalence between 3 seemingly different2 kinds of objects. I’ll start off by briefly introducing categories and sheaves 3; then I’ll say some things about covers, and finally get into the good stuff.

Categories and Sheaves (Sheafs?)

I’ve wanted to introduce categories on this blog for a long time now, but this is not the context in which I imagined I would do it. 4 Anyways, what’s a category?

- If $f\in\Hom_{\mc C}(A,B)$ and $g\in\Hom_{\mc C}(B,C)$ are morphisms, then there is a unique composite morphism $g\circ f\in\Hom_{\mc C}(A,C)$. Furthermore, composition of morphisms is associative so $h\circ(g\circ f)=(h\circ g)\circ f$ whenever either (and hence both) side is defined.

- For all $A\in\ob\mc C$, there exists an identity morphism $1_A\in\Hom_{\mc C}(A,A)$ such that, for all $B\in\ob\mc C$ all $f\in\Hom_{\mc C}(A,B)$ and all $g\in\Hom_{\mc C}(B,A)$, we have $f=f\circ1_A$ and $g=1_A\circ g$.

The notion of a category is very general; think of your favorite type of mathematical object and you can probably form a category out of these things. The goto first example of a category people see is $\mrm{Set}$, the category whose objects are sets and whose morphisms are set maps. However, while easy to understand, this is a terrible example becasue (1) nobody ever does math in the category $\mrm{Set}$ (sets are too unstructured) and (2) seeing this example makes it harder to internalize the fact that objects/morphisms are atomic as far as category theory is concerned (you’re objects don’t have to be sets, and your morphisms don’t have to be “structure-preserving” set maps). 5

As far as fixing (1) above, better examples to have in mind are $\mrm{Top}$, the category of topological spaces with continuous maps are morphisms; $\mrm{Ab}$, the category of abelian groups with group homomorphisms as its morphisms; and $R-\mrm{Mod}$ (here, $R$ is some ring), the category of left $R$-modules 6 with $R$-linear maps as its morphisms. For better examples as far as (2) is concerned, think about the following.

Category theory is all about studying objects through their properties and their interactions (i.e. maps) with other objects of the same type instead of through their particular construction. So if we want to study categories, we should study maps between categories.

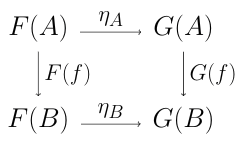

Now that we know what a functor is, we can form a (large) category $\mrm{Cat}$ whose objects are (small) categories and whose morphisms are functors, but why stop there? The real raison d’être of category theory is to look at categories whose objects are functors and whose morphisms are $\dots$7

Now, given two categories $\mc C,\mc D$, we let $\mc D^{\mc C}$ denote the category of (covariant) functors $\mc C\to\mc D$ with natural transformations as morphisms, and let $\mc D^{\mc C\op}$ denote the cateogry of contravariant functors $\mc C\to\mc D$ with natural transformations as morphisms.

I know I joked above about this stuff being abstract nonsense 8, but these functor categories are actually fairly natural and show up often; although, they’re not always presented as functor categories.

A morphism of presheaves $\msP,\msS$ on $X$ is a collection of maps $\msP(U)\to\msS(U)$ commuting with the restriction maps on $\msP,\msS$ respectively.

We’ll say more about (pre)sheaves in a bit, but before that, there’s a little more category theory to introduce. Anytime you define a mathematical object, you have to ask yourself what equivalence relation you want to consider them up to. For categories, there are (at least) 2 choices. The first is fairly obvious.

This turns out to be too strong a condition most of the time, so people usually only care about a weaker condition which you can think of as the homotopy equivalence of categories.

The goal of this post is to show that three certain categories are equivalent. One of these is the category of locally constant sheaves, so let us return to (pre)sheaves. 9

That definition is a bit of a mouthful because I tried to make it general, but then ran into the issue that not all categories are built from sets. To stop further confusion, for the rest of this section assume all presheaves (at the very least) spit out abelian groups because this is (almost) always true in practice anyway 10. A sheaf is a presheaf where given a consistent choice of elements $f_i\in\msP(U_i)$, you can always (uniquely) glue these to get a global elements $f\in\msP(\bigcup U_i)$. Now, sheaves are really good for studying local properties and studying their ability (or failure) to satisfy local-to-global principals. One notion that helps in studying local properties via sheafs is that of a stalk.

This post is looking like it might get quite long 11, so I’m just gonna move on without discussing stalks further except to say that, for our needs, they will appear as fibers of certain topological covers.

Sheaves are nice to have and work with, but presheaves are easier to write down. Thus, it’s really nice that there is a (functorial) process called sheafification that, given any presheaf $\msP$ spits out a sheaf $\msP^+$ with a morphism $\msP\to\msP^+$ inducing an isomorphism on stalks 12 such that any morphism $\msP\to\msS$ from $\msP$ to a sheaf $\msS$ factors uniquely as $\msP\to\msP^+\to\msS$. Let’s end this section with a simple example. Fix an abelian group $M$ and a topological space $X$. Let $M_X$ denote the constant presheaf, i.e. $M_X(U)=M$ for all $U\in\Open(X)$. 13 Its sheafification $M_X^+$ is the locally constant sheaf (which, because sheaves > presheaves, we still denote $M_X$ and we refer to as a constant sheaf) whose value on $U\in\Open(X)$ is $M\oplus M\oplus\cdots\oplus M$ where the number of factors of $M$ equals the number of connected components of $U$ 14. It would not be a bad idea to pause and go through the trouble of varifying that the constant presheaf really is a presheaf whose sheafification really is the constant sheaf as I have defined them.

Covers

Well, that last section felt like a lot of material to introduce all at once, so I really hope you’ve seen categories and/or presheaves before. 15 I think this one will be more digestible 16.

Let’s collect some facts about covers.

At this point, I should probably mention this section is about laying the ground work to show an equivalence of categories between covers of $X$ and $\pi_1(X,x)$-sets for “nice enough” $X$. To define the relavent functor, we’ll need a way to recover a $\pi_1(X,x)$-action from a cover of $X$.

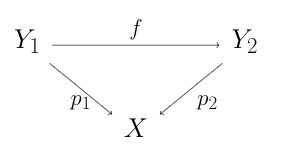

$\DeclareMathOperator{\Cov}{Cov}\DeclareMathOperator{\Fib}{Fib}$ For concreteness, let $\Cov(X)$ denote the category of coverings of $X$, and let $\pi_1(X,x)\mrm{-Set}=\mrm{Set}^{\pi_1(X,x)}$ denote the category of left $\pi_1(X,x)$-sets. We want to say that the above corollary gives the existence of a functor $F=\Fib_x:\Cov(X)\to\pi_1(X,x)\mrm{-Set}$ such that $F(p)=\inv p(x)$. However, we may worry that it is nonobvious that this construction comes with $\pi_1(X,x)$-equivariant induced maps (i.e. natural transformations) $F(f):\inv p_1(x)\to \inv p_2(x)$ where $f:Y_1\to Y_2$ is a cover morphism from $p_1:Y_1\to X$ to $p_2:Y_2\to X$. However, there is nothing to worry about. The obvious choice of $F(f):\inv p_1(x)\to\inv p_2(x)$ is $\pi_1(X,x)$-equivariant because of uniqueness of path lifting.

We’ll show that $\Fib_x$ is an equivalence of categories in the next section. To facilitate this, we’ll show that $\Fib_x$ is representable in the sense that $\Fib_x\cong\Hom_{\Cov(X)}(C,-)$ (this isomorphism taking place in the functor category $(\pi_1(X,x)\mrm{-Set})^{\Cov(X)}$) for some $C\in\Cov(X)$. To make $\Hom_{\Cov(X)}(C,D)$ a $\pi_1(X,x)$-set, give it the post-compose by (the action of) $\gamma\in\pi_1(X,x)$ action.

I think the construction of $\wt X_x$ is one of those things that becomes obviously the right choice after you see it and digest it, but that can be hard to succinctly motivate beforehand, so I won’t try to. As a general rule of thumb, let $I=[0,1]$ denote the unit interval.

Now, fix the point $\st x\in\wt X_x$ to be the homotopy class of the constant loop at $x$. We will show that the cover $p:\wt X_x\to X$ represents the functor $\Fib_x$. This means we need a functorial isomorphism $\inv q(x)\iso\Hom_{\Cov(X)}(\wt X_x,Y)$ for any cover $q:Y\to X$. For any such cover and any choice of $y\in\inv q(x)$, let $\pi_y:\wt X_x\to Y$ be the morphism taking a point $[f]\in\wt X_x$ to $\st f(1)$ where $\st f:[0,1]\to Y$ is the unique path lifting $f$ with $\st f(0)=y$. Note that this is $\pi_1(X,x)$-equivariant by uniqueness of path lifting. To see that this is an isomorphism, observe that the map $\phi\mapsto\phi(\st x)$ is an explicit inverse. Finally this map is functorial since given a morphism $Y\to Y'$ of covers of $X$ taking $y\in Y$ to $y'\in Y'$, the induced map $\Hom_{\Cov(X)}(\wt X_x,Y)\to\Hom_{\Cov(X)}(\wt X_x,Y')$ takes $\pi_y$ to $\pi_{y'}$ as these are the maps sending $\wt x$ to $y$ and $y'$, repsectively.

To make matters simpler, fix some path-connected and semilocally simply connected space $X$ with a choice of basepoint $x\in X$. The representing cover $\wt X_x$ coming from the above theorem is called the universal cover of $X$.

At this point, I think we have (almost) everything we need to show that covers of $X$ are the same thing as sets with a $\pi_1(X,x)$-action.

The First Equivalence

You may have noticed the “(almost)” in the previous sentence. That’s there because directly proving a functor gives an equivalence of categories is annoying since you need to give an inverse functor and two natural transformations. To help ease our pain, we’ll prove a lemma which says that the existence of one “nice” functor suffices to prove an equivalence of categories.

We will give a proof of the “if” direction, but leave the “only if” direction as an exercise.

I bet you can guess what comes next: to show that $\Fib_x$ gives an equivalence of categories, we’ll show that it is fully faithful and essentially surjective. We’ll prove each of these as a lemma, and then conclude what we want. Fix some path-connected and semilocally simply connected topological space $X$ with a chosen basepoint $x\in X$.

Whelp. I hope the journey was worth it. Probably if you’ve seen covering spaces before, this isn’t too surprising, but I think it’s still nice to see things from a more categorical perspective. I suspect that the next result is will be more surprising even to someone who has seen sheaves before (unless, of course, they’ve also seen this result before) 17: the category of (left) $\pi_1(X,x)$-sets is equivalent to the category of locally constant sheaves on $X$.

The Second Equivalence

Let’s get started. First off, I don’t think I mentioned this before (but I did use this terminology earlier), but if $\ms P$ is a presheaf and $U\subseteq X$ is open, then any $s\in\msP(U)$ is called a section of $\msP$ (defined) over $U$. This is because “sheaves of sections” (this use of “section” refering to (local) right inverses) show up fairly regularly in math 18. As an example

Now, recall that a constant sheaf $\msS=S_X$ is the sheafification of the presheaf of constant functions to some fixed set $S$ (i.e. $\msS(U)$ is the set of locally constant functions $U\to S$). You may object that these should really be called locally constant sheaves; I hear that objection, ignore it, and make the following definition just to make the situation more confusing.

$\DeclareMathOperator{\LCS}{LCS}$ Note that a morphism $\phi:Y\to Z$ of covers of $X$ induces a morphism $\ms F_Y\to\ms F_Z$ of locally constant sheaves by taking the local section $s:U\to Y$ to $\phi\circ s$ ($\phi\circ s$ is a local section precisely because $\phi$ is a cover morphism) 19. Hence, we get a functor $S:Y\mapsto\ms F_Y$ from the category $\Cov(X)$ of covers of $X$ to the category $\LCS(X)$ of $\mrm{Set}$-valued locally constant sheaves on $X$. To show that this functor gives an equivalence of categories we’ll just construct an inverse this time. This is where we get to make use of stalks.

Let $X$ be a topological space, and let $\ms F$ be a presheaf (of sets) on $X$. Let \(X_{\ms F}=\bigsqcup_{x\in X}\ms F_x\) be the disjoint union of the stalks of $\ms F$. We want to give this set a topology. Note that for any open $U\subset X$, a section $s\in\ms F(U)$ gives rise to a map $i_s:U\to X_{\ms F}$ sending each $x\in U$ to the germ $s_x\in\ms F_x$ of $s$ over $x$. Give $X_{\ms F}$ the coarsest (i.e. smallest) 20 topology in which the sets $i_s(U)$ are open for all $U$ and $s$. Let $p_{\ms F}:X_{\ms F}\to X$ be the map sending a germ to the point over which it is defined (i.e. $p_{\ms F}\mid_{\ms F_x}=x$ for all $x\in X$). This map is continuous because \(\inv p_{\ms F}(U)=\bigcup_{s\in\ms F(U)}i_s(U)\) is open. Furthermore, the maps $i_s:U\to X_{\ms F}$ are continuous as well, and I’ll leave this for you to check. Note that a morphism $\phi:\ms F\to\ms G$ of presheaves induces maps $\ms F_x\to\ms G_x$ for each $x\in X$, and hence a set map $\phi:X_{\ms F}\to X_{\ms G}$ compatible with the projections onto $X$. Thus, the assignment $\ms F\mapsto X_{\ms F}$ gives a functor from the category of sheaves on $X$ to the category of spaces over $X$ (Technically, we need to show that $\phi$ is continuous, but this is easy).

Now that we have our inverse functor, we prove.

There you have it. A locally constant sheaf on a space $X$ is nothing more than a cover of that space or, if it is nice enough, a (left) $\pi_1(X,x)$-set. To end this post, try proving the following

For motivation for why you might care about this, fix a field $k$, and recall that a linear representation $\rho:\pi_1(X,x)\to\GL_n(k)$ of the fundamental group of $X$ is the same thing as a choice of a $k[\pi_1(X,x)]$-module $M$ (i.e. there’s an equivalence of categories between linear representations and modules over the group ring). With this in mind, the above exercise asks you to show that a locally constant sheaf of $k$-modules on a (sufficiently nice) space $X$ is the same thing as a representation of its fundamental group! 21

-

As a rule of thumb, if I ever say that I will write a post about something, you probably shouldn’t believe that I will actually follow through with that promise. ↩

-

Admittedly, the first two are unsurprisingly related ↩

-

If you know what these are, just skip the first section or two ↩

-

Always thought it would be in some blog post about $R$-modules and I thought I would not be doing you the disservice of talking about categories without mentioning universal properties. Oh well… it just goes to show ↩

-

The irony (or not irony? What does this word even technically mean?) of $\mrm{Set}$ technically being the first example I give is not lost on me. ↩

-

The category of right $R$-modules is written $\mrm{Mod}-R$. ↩

-

There’s a reason people call this stuff abstract nonsense ↩

-

If you don’t remember me doing this, then you really gotta start reading these footnotes ↩

-

You might be wondering if one can define sheaves for categories without forgetful functors to Set. I imagine that the answer to this is yes and that one way to do this is by viewing the elements of an object $A$ in you category as the morphisms $B\to A$ for various $B$ a la this. Alternatively, maybe you can do something like say $\msP$ is a sheave if given any collection $\bracks{U_i}$ for $i\in I$ of open sets, the category whose objects are $\msP\parens{\bigcap_{j\in J}U_j}$ for finite $J\subseteq I$ has all colimits (in the categorical sense). I haven’t thought about this enough to know if either of these work (or if they recover the usual definition when the objects in your category secretly are sets) ↩

-

When we get into the meat of things, we’ll actually be looking at $\mrm{Set}$-valued sheaves ↩

-

We’re still in the prelims (!) ↩

-

Exercise convince yourself that any morphism $\ms A\to\ms B$ between presheaves induces a morphism $\ms A_x\to\ms B_x$ on stalks. ↩

-

Think of this as the presheaf of constant functions $X\to M$. ↩

-

i.e. $M_X(U)=M^{\oplus\dim\hom_0(U,\R)}$ ↩

-

I’m starting to understand why people write textbooks instead of just trying to jam everything into individual blog posts. Maybe I should take a page from Jeremy Kun’s playbook and start separating all the background material into their own separate posts. ↩

-

I’m assuming you’ve seen fundamental groups before, so probably you’ve also seen covering spaces and this section is mostly review ↩

-

My introduction to sheaf theory was somewhat nonstandard, so it’s possible that this is a commonly taught/known result and I just happened to be out of the loop until recently ↩

-

e.g. when proving that the category of vector bundles on a space is equivalent to the category of locally free sheaves on that space ↩

-

Show rigorously that this is a well-defined map of sheaves (hint: because these things are sheaves to show that $\phi\circ s$ is a section, it suffices to show that it restricts to a section on each set in an open cover of $U$) ↩

-

I don’t think I’ll ever be able to remember which of “coarser” and “finer” means smaller without pulling up Wikipedia. ↩

-

(I’m pretty sure that) It is possible to recover a group from its category of $k$-linear representations, so perhaps if you wanted to define a version of the fundamental group in algebraic contexts where you have a not-so-nice topology, you should try giving a definition in terms of locally constant sheaves of that space (or in terms of covers of that space). ↩