I’ve recently been skimming through this book called “Office Hours with a Geometric Group Theorist” which, perhaps unsurprisingly, is about using geometric objects to study groups. It mostly focuses on how group actions on graphs and metric spaces can reveal information about the group1, and contains some pretty nice results. Unfortunately, I have too many in mind for one post, but I would still like to introduce the basic notions of the subject and a few results I enjoyed. I imagine this will be a lengthy post with a mix of introducing theory and neat applications2.

Groups Actions 3

While I didn’t emphasize this much then, towards the beginning of my intro post on group theory, I mentioned that groups often “perform some action on an object.” Here is where we’ll get to see what I meant and why this is useful.

- $1\cdot x=x$ for all $x\in X$ where $1\in G$ is the identity

- $g\cdot(h\cdot x)=(gh)\cdot x$ for all $x\in X$ and $g,h\in G$

In essence, a group action is an action of $G$ on $X$ (i.e. a function $G\times X\rightarrow X$) that respects the group structure of $G$. Above, $X$ is just a set so this is all we require. When we later look at actions on graphs or metric spaces, we’ll further require that $G$’s actions preserves $X$’s structure4.

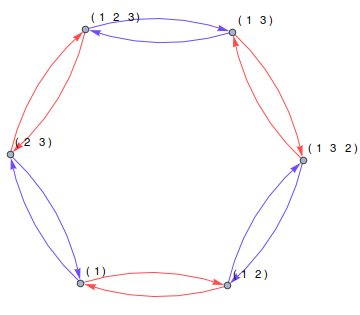

One of the most basic examples of a group action comes from symmetric groups. Given a set $X$, its symmetric group $S_X$ is $S_X=\{f:X\rightarrow X\mid f\text{ bijective}\}$ with composition as the group operation. This has a natural action on $X$; namely $f\cdot x=f(x)$. If you want, you can verify that this gives a group action, but it is pretty tautological. When $X$ is just a set, there’s no additional structure to preserve so we think of its symmetries as just being permutations; hence the name of the above group. When you think about it, for any group action $G\curvearrowright X$, each $g\in G$ induces a function $X\rightarrow X$ and this function turns out to be a permutation. Thus, we have the following Prove that a group action $G\curvearrowright X$ is the same thing as a group homomorphism $G\rightarrow S_X$. If this homomorphism is injective, then we say that the action is faithful. As a corollary to this exercise, we get the following Every group is isomorphic to a subset of a symmetric group. Let $G$ be a group. By the above exercise it suffices to show that $G$ acts faithfully on some set $X$. We can simply take $X=G$ with action given by left multiplication (i.e. $g\cdot h=gh$). This action is faithful since every $g\in G$ acts differently on the identity, so we win. When studying general group actions, there are two basic concepts of extreme importance. Let $G$ be a group acting on a set $X$. Given some $x\in X$, its orbit is \(G\cdot x=\{g\cdot x\mid g\in G\}\) Furthermore, its stabalizer (or stabalizer subgroup) is \(G_x=\{g\in G\mid g\cdot x=x\}\) Personally, I like to think of orbits and stabalizers in terms of graphs. Given an action $G\curvearrowright X$, you can form a graph with vertex set $X$, such that for each $(x,g)\in X\times G$ you get an edge from $x$ to $g\cdot x$. In this language, orbits are connected components of this graph and (elements of) stabalizers correspond to self edges. 5

The following two theorems 6 are good to know for general group action knowledge, but I do not believe either will be used in this post, so I won’t bother proving them here. Let $G$ be a group acting on $X$. Fix some $x\in X$. Then, \(|G\cdot x|=|G:G_x|=\frac{|G|}{|\Stab(x)|}\) Let $G$ be a finite group acting on a set $X$. For $g\in G$, let $X^g=\{x\in X\mid g\cdot x=x\}$ be the elments fixed by $g$, and let $X/G$ denote the (set-theoretic) quotient of $X$ by the equivalence relation $x\sim y\iff x\in G_y$. Then, \(|X/G|=\frac1{|G|}\sum_{g\in G}|X^g|\) To finish this section, I’ll mention a few definitions that should come up in this post. There are a few types of group actions. In the first exercise above, I defined what a faithful action is already; two more of importance are transitive and free actions. A group action $G\actson X$ is called transitive if $G\cdot x=X$ for some (equivalently, all) $x\in X$. The action is free (or $G$ acts freely on $X$) if $\Stab(x)$ is trivial for all $x\in X$ (i.e. no non-trivial element of $G$ fixes any element of $X$) We’ll see that free actions in particular reveal algebraic information about the group involved.

Graphs

If we’re gonna study groups through their actions, then we’re gonna need objects for them to act on. Sets are all well and good, but are too unrestrictive. The more structure we require on the objects we act on, the more we will have at our disposal to gain information from.

To begin, we will remind the reader of what a graph is, and then introduce how groups act on them. A graph $G=(V,E)$ is pair consisting of a set $V=V(G)$ or vertices and a set $E=E(G)\subseteq V\times V$ of edges. If $(u,v)\in E\iff(v,u)\in E$ for all $u,v\in V$, then we say $G$ is undirected. If $(v,v)\not\in E$ for all $v\in V$, then we say $G$ is simple.

If you don’t already know them, look up definitions for paths, connected graphs, and trees. 7

Graphs are hardly ever written down in terms of explicit vertex and edge sets. More commonly, they are given as some drawing.

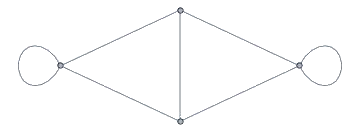

Below is an example of an undirected (but not simple) graph

To make this part of the proof simple, we'll need to impose one further restriction on our automorphisms: they must preserve edge labels (e.g. $(g,gs)\in E\iff(\phi(g),\phi(g)s)\in E$ for $\phi\in\Aut(\Gamma)$ where $s\in S$ is regarded as the label of that edge). Now, consider an arbitrary $\phi\in\Aut(\Gamma)$ and write $\phi(v_e)=v_g$ where $e$ is the identity. Fix some vertex $v_h\in V(\Gamma)$. We will show that $\phi(v_h)=\phi_g(v_h):=v_{gh}$ by inducting on the length of the shortest (not necessarily directed) path from $v_e$ to $v_h$. This obviously holds when the path has length 0, so suppose the path has length $n>0$, so we can write $h=ws$ where there's a path of length $n-1$ from $v_e$ to $v_w$ and $s\in S$. By our inductive hypothesis, $\phi(v_w)=\phi_g(v_w)=v_{gw}$ so $\phi$ carries the edge $(v_w,v_h)$ to the edge $(v_{gw},v_{gws})$ to $\phi(v_h)=v_{gws}=v_h$ and hence $\phi=\phi_g$, proving the claim.

When inducting in the above proof, we claim that $s\in S$, but in actuality, it’s also possible that $\inv s\in S$ instead. Finish the proof by handling this case.

In the above proof, we assume that automorphisms preserve edge labels. Does the theorem still hold without this extra assumption (hint: 9)?

This realizes every group as the symmetries of some graph. Hence, even the most abstract groups have some kind of concrete realization.

Metric Spaces

We’re almost to the first nice result; I promise. Before we can state it though, I need to introduce the concept of a Metric space and how they’re acted on by groups. Intuitively, a metric space is anywhere you have some notion of distance.

- positive definitedness: $d(x,x)\ge0$ for all $x\in X$ with equality iff $x=0$

- symmetry: $d(x,y)=d(y,x)$ for all $x,y\in X$

- triangle inequality: $d(x,y)\le d(x,z) + d(z,y)$ for all $x,y,z\in X$

- Euclidean space $\R^n$ with the Euclidean metric $$d((x_1,\dots,x_n),(y_1,\dots,y_n))=\sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^n|x_i-y_i|^2}$$

- Euclidean space with the taxicab metric $$d((x_1,\dots,x_n),(y_1,\dots,y_n))=\sum_{i=1}^n|x_i-y_i|$$

- Any graph $\Gamma$ (really just its vertex set $V(\Gamma)$) with the path metric, where the distance bewteen any two vertices is the length of the shortest path between them.

The next example is of particular importance, and it also a bit surprising at first.

There’s actually an alternative way to think of this metric 10. Let $\inv S=\{\inv s\mid s\in S\}$ and define the word length of an arbitrary $g\in G$ to be the length of the shortest word in $S\cup\inv S$ that is equal to $g$. Then, we can turn $G$ into a metric space where the distance between $g,h\in G$ is the word length of $\inv gh$.

Naturally, we have a notion of a symmetry of a metric space coming from ways of viewing a metric space as equivalent to itself.

- $\zmod n$ acts on $\R^2$ with the Euclidean metric via rotations

- $\Z^n$ acts on $\R^n$ with the Euclidean or taxicab metrics by translations

- $S^4$ acts on a tetrehdron by permuting its vertices

- Every group acts on itself with the word metric by left multiplication

Finally, let’s see how actions can be used to reveal algebraic information about groups.

First Neat Application

Before I introduce our first real application of these ideas, I need to introduce one more definition.

Now, our goal of this section will be to prove the following theorem

Take a moment to let that sink in; from a almost purely geometric situation (a group acting on a metric space), we can make a non-trivial algebraic conclusion. This is a central theme of Geometric Group Theory, and more examples of this will be seen in this post11. For this particular theorem, the proof relies on the following lemma

Let $S\subseteq\R^n$ be some collection of points. A centroid12 of $S$ is a point $w\in\R^n$ minimizing \(\sum_{s\in S}d(w, s)^2\) Note that $w$ may not exist if $|S|=\infty$

With that Lemma, our theorem will actually have a fairly short proof

Free Groups and Presentations

For the next application I want to cover, we need a little more group theory. Specifically, we need to define free groups, and since it would be a shame to introduce free groups without introducing presentations, we include them here too. The idea behind free groups is that they’re essentially the bare minimum of what’s needed to call something a group; they don’t satisfy any non-trivial relations. We will begin with the definition of a free group, and then give a “categorical” (or “universal”) characterization of them.

Free groups can take a while to wrap your head around. I remember I used to be enamored with group theory because from so few axioms (only like 3 or 4), you were guaranteed to get an object that was really well-behaved with so much structure, but that all ended when I learned about free groups13. Free groups, and by extension general (non-abelian) groups 14, are trash; they can have too much freedom and/or unintuitive structure. It’s not all bad though; this makes results involving them feel extra interesting.

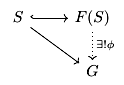

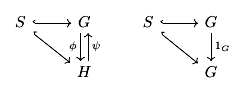

This construction of free groups is nice (and necessary), but we could alternatively choose to characterize free groups in terms of a so-called universal property. This has the advantage of including only the defining properties of a free group without tying the definition to any particular construction.

This universal property of free groups gives a natural segway into our next topic. Intuitively, a presentation of a group is a compact way of writing it down. Instead of specifying every single element and how to multiply them, you only write down some set of generators and relations (e.g. words equivalent to the identity). The notation looks like

\[G\simeq\pres{\text{generators}}{\text{relations}}\]so for example, we have $F_1\simeq\gen{a}\simeq\Z$ and $\zmod n\simeq\pres{a}{a^n}$. In order to formalize this, we make use of the following theorem.

Now, given a group $G$, in order to write down a presentation for it, we first find some free group $F(S)$ and normal subgroup $K\le F(S)$ s.t. $G\simeq F(S)/K$. Then, letting $R\subset K$ be a generating set for $K$, our presentation is

\[G\simeq\pres SR\]giving a formal definition of the notation15

Second Neat Application

Now that we’re a bit more aquainted with how horrible general groups can be, let’s focus on something a bit more familiar

\[\DeclareMathOperator{\SL}{SL}\SL_2(\Z)=\brackets{\left.\mat abcd\right| ad-bd=1}\]The group of $2\times2$ matrices with integer coordinates and determinant $1$. Linear algebra is a particularly nice subject, and this is a very linear algebraic group, so it must certainly be really nice, right?

Like I said, general groups are trash. This application will be similar to the last; we’ll prove a lemma that will give us a direct route to this theorem.

The above proof is a gem in and of itself, because it’s so clean. In case some clarity is lost in its brevity, the idea is that as you apply each syllable (i.e. $a^*$ or $b^*$) of $g$ to $X_b$, you keeping moving back between $X_b$ and $X_a$ (like a game of ping-pong), landing away from where you started. This simple lemma will let us prove this section’s main theorem in a rather concrete way.

Results for Future Posts

I mentioned in the beginning that I wouldn’t be able to cover all the results I would like. In this final section, I waat to mention some of things I left out.

An immediate application of this lemma16 is the following

While this fact may seem obvious or benign, it is definitely non-trivial. As an attempt to appreciate this tree lemma, I challenge you to prove this theorem completely algebraically (Spoiler: 17).

Keeping in touch with the theme of free groups, another surprising result is that $\SL_2(\Z)$ actually contains many more free groups than the one I pointed out in the last section.

This theorem is actually also proved by exhibiting a free action of this group on a tree.

Moving away from free groups, there’s a notion similar to an isometry but weaker called a quasi-isometry.

This theorem is particuarly interesting because it is highly geometric (or at least, the premise is). It is unclear how to even formulate this theorem algebraically if such a thing can be done.

As the name of this section suggests, I may return to give actual proofs of some of these results in a future post, but for now, I think this post has gone on long enough.

-

I haven’t looked into the book too deeply yet, so maybe this changes towards the end ↩

-

Plus many exercises (don’t feel pressured to do them all) ↩

-

This section was originally titled “Groups aren’t abstract nonsense” with the title of the post being “Geometric Group Theory”. While writing it, I decided that the concreteness of groups was a recurring-enough theme to be reflected in the title. Secretly though, groups are just groupoids (categories where every morphism is an isomorphism) with one object, so they actually are abstract nonsense. ↩

-

This won’t come up here, but it’s worth mentioning that much of representation theory is simply the study of group actions, and specifically, groups acting on vector spaces ↩

-

I want to make and insert an explicit example image of this, but was too lazy to do so. Hence, I encourage you to do this yourself with the group D_8 (symmetries of a square) acting on a regular octagon ↩

-

Burnside was not the first to prove this lemma. He, himself, attributed it to Frobenius but even before Frobenius, it was known to Cauchy. I do not know if Cauchy was the first to prove it or not. ↩

-

Honestly, half of graph theory is just setting up definitions. Also, shameless plus, I defined 2/3 of these in a previous post ↩

-

Recall two sets are the same when there’s a bijection between them, and the symmetrices of a set are the bijections to itself ↩

-

I don’t actually know the answer to this, but I suspect it doesn’t; at the very least, when trying to prove it without this assumption, I ran into issues showing that edge labels can’t change. If you decide to look for a (small) counterexample, I believe (but do not know for sure) than one should exist among finite groups with two or three generators ↩

-

Worth mentioning that we’ve just turned any group into a geometric object: a metric space ↩

-

Mostly referenced without proof at the very end ↩

-

The book (pg. 40) seems to define a centroid as the minimizer of the sum of distances (not squared distances) ↩

-

Interestingly enough, I had the opposite experience with linear algebra. At first I thought abstract vector spaces were cool because they were so abstract and potentially wild. When I first saw that every vector space had a basis, it ruined linear algebra for me because all these strange, crazy things I had been dealing with were essentially just R^n in disguise ↩

-

i.e. groups you may not see in your first exposure to group theory. ↩

-

To get a group from it’s presentation, just take the free group on its generators and quotient out by the smallest normal subgroup containing all the relations ↩

-

Maybe plus the fact that free groups have (infinite) trees for Cayley graphs ↩

-

There are ways other ways to prove this, but all the ones I know are geometric ↩