When I was a freshman in high-school1, my math teacher showed me this site where you can find a seemingly endless supply of math problems; I loved it. I spent a decent amount of my time solving problems, and a significant amount of my time failing to solve problems, but I enjoyed it either way. On the site, there are different categories, and you have a level from 1-5 in each category, indicating how well you do at solving those problems. After a while on the site, I came to be level 5 in number theory2, and was pretty shocked. I had barely heard of this “number theory” field, and wasn’t sure what about it made me do well3, so even before I had an idea of what number theory was, it seemed like a interesting field.

In general, I feel like number theory is a relatively unknown field to most people, so this is my little part in changing that. This post is probably gonna be a long one. In it, I want to talk about two (hopefully somewhat motivated) problems that lead to some interesting mathematics. Because I want to do the mathematics justice, I will try my best to keep the post self-contained, proving any non-trivial claims I make4. If you are more interested in the results/overall argument than the details, you can skip these.

Pythagoras

The Greeks seem like as good a place as any to start, and in the context of mathematics, one of the most famous Greeks in Pythagoras with his theorem.

Pythagoras’ Theorem

Given a right triangle with side lengths of \(a,b\), and \(c\) where \(c>a,b\), the following relation holds:

\(a^2 + b^2 = c^2\)

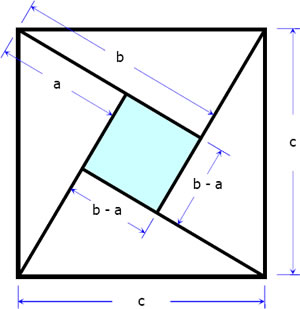

I said I would try to prove any non-trivial claim I made, and this theorem has always struck me as non-trivial. However, it is also pretty well known so I’ll just leave you with a picture and a link to the site I stole it from instead5.

Now that we have this, this lets us see that we can have a right triangle with side lengths \((3,4,5)\), \((5,12,13)\), \((21,28,35)\), or \((7,24,25)\) but not one with side lengths \((1,2,3)\) or \((4,4,4)\). In fact, if we think about it, this says we can’t have any equilateral right triangle. If we did and the side length was \(x\), then this would give \(x^2+x^2=x^2\implies 2x^2=x^2\implies x=0\), and a triangle with 0 side length is no triangle at all. I think a natural question to ask at this point would be “what side lengths can we get?”. Now, we have to be careful about how we phrase this, because obviosly given any \(a\) and \(b\), we can find some \(c\) that gives a right triangle, but that \(c\) may not be nice. For example, if \(a=2\) and \(b=4\), then \(c=\sqrt{a^2+b^2}=\sqrt{20}=2\sqrt5\) isn’t the nicest looking solution. What we really want is a triangle where all side lengths are whole numbers.

Question

What are the triples of integers \((a,b,c)\) where \(a,b,c\in\mathbb Z\)6 such that \(a^2+b^2=c^2\)?

One possible issue worth addressing is that this phrasing allows for negative integers. I said before that a “triangle with 0 side length is no triangle at all”; well, a triangle with negative side length seems like it should be even less qualified to answer the question. However, there are a few good reasons to allow negative (and even zero) side lengths as I’ve done with this question:

-

Worse case scenario, they can be igonored. Squaring erases information about sign, so if you have a negative number in a solution, just negate it to get a solution with only positive numbers. If you have a zero, then you just have \(a^2=c^2\implies a=\pm c\), so your solution can be considered “trivial” and just ignored. There’s no harm done here.

-

Working with all integers instead of just the positive integers adds symmetry to the problem. Symmetry and patterns and whatnot are usual good in math, so including them can make finding a solution easier.

-

They have geometric interpretations. If a solution includes \(0\), then the right triangle you are describing is actually just a line segment. If it includes negative numbers then your the signs of numbers describe its orientations. You can imagine \((3,4,5)\) as a triangle pointing to the right while \((-3,4,5)\) points to the left.

Progress

Now that we have a question we’re happy with, how do we actually go about solving it? In my reasons for using all the integers instead of just the positive ones, I said that the whole integers were nicer than the positive integers. While this is true, they still aren’t super nice. When you think about, you can only add, subtract, and multiply integers. You can’t really divide them, so we’ll have to be careful about what algebra we do. With that in mind, let’s see what progress we can make.

If you play with this equation for a while, trying to find solutions and seeing what comes up, you might notice a pattern. Looking at the four solutions I gave earlier, we see both \((3,4,5)\) and \((21,28,35)\). The second of these is \(7\) times the first, and this leads into the following observation.

Lemma

If \((a,b,c)\) is a Pythagorean triple and \(n\in\mathbb Z\), then \((an,bn,cn)\) is a Pythagorean triple as well

What this means is that in our search for integer solutions, we really only need worry about ones where \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\) have no common factors.

Exercise

If two of \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\) share a common factor \(d\), then \(d\) divides the third one as well.

This is a start. From now on, we’ll implicitly assume the numbers we’re working with are coprime7. Returning to our issue with integers, we can’t divide them, but we know that if we do we’ll get a rational number, and fractions are even nicer then integers. This leads to the following simple yet profound algebraic manipulation.

\[\begin{align*} &a^2 + b^2 = c^2 \implies \frac{a^2}{c^2} + \frac{b^2}{c^2} = 1 \implies \left(\frac ac\right)^2 + \left(\frac bc\right)^2 = 1\\ \text{Conversley, } &\left(\frac ac\right)^2 + \left(\frac bc\right)^2 = 1 \implies \frac{a^2}{c^2} + \frac{b^2}{c^2} = 1 \implies a^2 + b^2 = c^2 \end{align*}\]When we do this, \(\frac ac\) and \(\frac bc\) are fractions in simplest form since this goes both ways, this means that finding (coprime) integer solutions to \(a^2+b^2=c^2\) is equivalent to finding rational solutions to \(A^2+B^2=1\)! It get’s even better than this.

Lemma

The rational \(A,B\) satisfying \(A^2+B^2=1\) are exactly the rational points \((A,B)\) on the unit circle.

8Stop and think about this for a second. We have shown that the number theoretic problem finding all integer solutions to \(a^2+b^2=c^2\) is equivalent to the geometric problem of finding all rational points on the unit circle. This is a major shift in perspective and will directly lead into the insight that allows us to answer our question.

Solution

When giving a mathematical argument on here, I’m always a little stumped on how to motivate to main idea. I would like to give the impression that there’s nothing magical or other worldly going on here; that given enought time to think about it, you could have produced everything I do here. What follows is my best attempt to do that.

Now that we know that we’re finding points on a circle, let’s try to use some geometric intuition. If you look at the circumference of a circle, it’s really just a line that’s been wrapped around to connect to itself, and while circles can be complicated to work with, lines are pretty simple objects. Imagine if we could uncurl the circle back into a line. Then, ideally, all the rational points on the circle would end up laying exactly on top of a rational number on the line, and this would let us find the rational points of a circle by looking at the rational points of the number line (which are just the fractions). What we’ll be doing is essentially the following

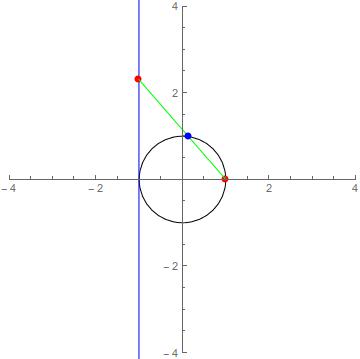

To describe this mathematically, we need to decide how we’ll uncurl the circle. We want to manipulate the circle until it lies along the number line, but there are many ways to draw a line in the plane, so we need to choose one. Any will work, but following the animation’s example, we’ll use the line \(x=-1\). Now, we need a choice of reference point, where we’ll begin our uncurling. You can imagine that if we unzipped the circle from the point \((0,1)\) then \(\sim\frac34\) of it would end up below the \(x\)-axis and only \(\sim\frac14\) would end up above the \(x\)-axis. Because we like to keep things simple and symmetric, we’ll unzip from the point \((1,0)\).

Now we’re ready for some algebra. What we’re realing doing here to unzip the circle is drawing lines through it. Our goal is to end up on the line \(x=-1\), so start with the point \((-1,t)\) where \(t\in\mathbb Q\) is an arbitrary rational number. We want to relate this to a (rational) point on the circle. Since we chose \((1,0)\) as our reference, we’ll do this by looking at the line \(t(X-1)=-2Y\) through both \((-1,t)\) and \((1,0)\). This line will intersect the circle \(X^2+Y^2=1\) in one other place, and this will be the rational point associated to \(t\).9

At this point, things look good but you have to believe me that our line will intersect the circle in a second point, and that this point will also be rational. Visually, I think it’s easy to see that the line will have a second point of intersection with the circle. If you want something a little more rigourous…

Lemma

The line \(t(X-1)=-2Y\) where \(t\) is rational intersects the circle \(X^2+Y^2=1\) in two rational points.

All that’s left to do is actually make this substitution and solve for \(X\) and \(Y\) given \(t\). We have

\[\begin{align*} t(X-1)=-2Y &&& X^2+Y^2=1\\ t^2(X-1)^2=4Y^2 &&& 4X^2+4Y^2=4\\ && t^2(X^2-2X+1)=4-4X^2\\ && (t^2+4)X^2-2t^2X^2+(t^2-4)=0 \end{align*}\]At this point, we could follow the proof and use the quadratic formula, but I’d rather introduce something new called Vieta’s formulas.

Theorem (Vieta)

If the polynomial \(f(X)=a_nX^n+a_{n-1}X^{n-1}+\dots+a_1X+a_0\) has roots \(\lambda_1,\lambda_2,\dots,\lambda_n\), then \(\lambda_1+\lambda_2+\dots+\lambda_n=-a_{n-1}/a_n\).

This theorem is useful because we know that \(X=1\) is a root of the complicated polynomial we have (corresponding to our reference point \((1,0)\)), so whatever the second root \(X\) is, we know we must have

\[\begin{align*} X+1=\frac{2t^2}{t^2+4} &\implies X=\frac{t^2-4}{t^2+4}\\ &\implies Y=\frac{-t}2(X-1)=\frac{4t}{t^2+4} \end{align*}\]This seems like another good place for a quick pause. What we have just done is found a way to turn a rational number \(t\) into a pair of rational numbers \((X,Y)\) on the unit circle which can be turned into 3 coprime integers \((X,Y,Z)\) that satisfy the Pythagorean theorem. In essence, we have found a 1-1 correspondence between fractions and rational points on the circle 10 which solves our problem by our earlier observation that rational points on the circle are in 1-1 correspondence with coprime Pythagorean triples.

To finish up, we’ll note that a rational number is really just two integers as we can write \(t=\frac mn\) where \(m,n\in\mathbb Z\) are coprime. Thus, to form any Pythagorean triple, pick any two integers \(m,n\) and use calculate the following: \(\left(\frac{t^2-4}{t^2+4},\frac{4t}{t^2+4}\right)=\left(\frac{(m/n)^2-4}{(m/n)^2+4},\frac{4m/n}{(m/n)^2+4}\right)=\left(\frac{m^2-4n^2}{m^2+4n^2},\frac{4mn}{m^2+4n^2}\right)\) which corresponds to the solution11

\[\begin{align*} (a,b,c)=(m^2-4n^2,4mn,m^2+4n^2) \end{align*}\]All Pythagorean triples can be generated this way with the caveat that you may have to swap \(a\) and \(b\), negate one (or both) of them, or scale both of them up by a constant factor.

Gauss

There is a nice connection between the second thing I wanted to talk about and the first, but unfortunately, I cannot remember it so I don’t have a good segway into this topic like I wanted to. I will still mention that one of my favorite identites from algebra was always different of squares: \(a^2-b^2=(a-b)(a+b)\), and in fact, if you look at the Pythagorean problem, it was essentially a fancy difference of squares problem. We had \(a^2+b^2=c^2\) which just means that \(a^2-(-b^2)=c^2\). The issue with factoring this like before is having to take a square root of \((-b^2)\). This isn’t a big issue though. You can extend the real numbers to a bigger set of numbers called complex numbers that includes a number \(i\) such that \(i^2=-1\). Allowing for use of \(i\), we can write \(a^2+b^2=c^2\) as \((a+bi)(a-bi)=c^2\). In fact12, you can use this to derive a formula for all Pythagorean triples instead of taking the approach we did above. If nothing else, that should be indication that this \(i\) is something worth studying.

Since we’re doing number theory, instead of looking at all complex numbers, we’ll focus on a subset called the Gaussian integers; these are the numbers \(a+bi\) where \(a,b\in\mathbb Z\). As their name suggests, these numbers play an analagous role to the normal integers as a subset of the real (or just rational) numbers. One of the most important aspects of the normal integers is the behavior of prime numbers, so we’ll investigate the analgous behavior for Gaussian primes. In particular, we’ll ask the following question

Question

Which primes \(p\in\mathbb Z\) remain prime we viewed as the Guassian integer \(p=p+0i\in\mathbb Z[i]\)

To get a feel for this question. Let’s try to factor the first few primes and see what happens. After some trial and error, you might end up with a table like

\[\begin{matrix} 2=(1+i)(1-i) & 3=3 & 5=(2+i)(2-i)\\ 7=7 & 11=11 & 13=(3+2i)(3-2i)\\ 17 = (4+i)(4-i) & 19=19 & 23=23\\ & \vdots \end{matrix}\]The primes that can be factored seem pretty random, but the way in which they are factored has a pattern to it.

Aside

When I introduced \(i\), I said that \(i^2=-1\) which means that \(i\) is a square root of \(-1\). However, every number has two square roots, and indeed \((-i)^2=(-1)^2(i)^2=1(-1)=-1\), so \(-1\) is no exception. However, when I defined \(i\), I just said it was a square root of \(-1\) without specifying which. You can imagine swapping \(i\) with \((-i)\) everywhere you use it, and this shouldn’t change whether what you have is true or not since \(i\)’s defining feature (having \(-1\) as a square) doesn’t define it uniquely. This could make you think that there might be ways of combining \(i\) and \(-i\) to gain information about numbers.

Noticing this pattern, and the aside above, we make the following definition (whenever I write something like \(a+bi\), just assume that \(a\) and \(b\) are normal integers. I won’t bother always specifying.)

Definition

Given a number \(a+bi\in\mathbb Z[i]\), we define its norm to be \(N(a+bi):=(a+bi)(a-bi)=a^2+b^2\). Note that the norm of a number is always a non-negative integer.

This function has the nice property of being multiplicative

Lemma

\(N((a+bi)(c+di))=N(a+bi)N(c+di)\)

With this definition under our belt, we see that the primes that are no longer prime factor as the norm of a number, and so can be written as the sum of two squares. Does this hold in general? Before answering this, a quick remark. When we factor numbers in the normal integers, there is always the issue of \(-1\). If we write \(15=3(5)\), then we could alternatively write \(15=(-3)(-5)\). Similarly, if we write \(7=7(1)\), we could also write \(7=7(-1)\). Despite this, we still like to say \(15\) has a unique factorization and \(7\) has no factors other than 1 and itself. What’s going on here is that \(-1\) divides \(1\) so no matter how we factor something, we can always just absorb extra \(-1\)’s into the factorization. This shouldn’t count as really being a different factorization, so we characterize annoying numbers like this as follows

Definition

A number \(u\) that divides \(1\) is called a unit. Equivalently, if there exists a number \(v\) such that \(uv=1\), then \(u\) is a unit.

When we talk about factorization, we don’t care about units. Furthermore,

Theorem

In \(\mathbb Z[i]\) the only units are \(\pm1,\pm i\), and a number \(x\) is a unit if and only if \(N(x)=1\)

For the first part of the theorem, assume \(u\) is a unit and write \(u=a+bi\) so \(a^2+b^2=1\). Clearly, either \((a,b)=(1,0)\) or \((a,b)=(0,1)\) so the claim holds. \(\square\)

Theorem

(Normal) prime \(p\) factors in \(\mathbb Z[i]\) if and only if \(p\) can be written as the sum of two squares.

(\(\leftarrow\)) If \(a^2+b^2=p\), then \(p=(a+bi)(a-bi)\).\(\square\)

This means we can classify the normal primes that are Gaussian primes by figuring out which can be written as the sum of two squares. This turns out to have a surprising answer using some modular arithmetic.

Theorem

An odd prime \(p\) can be written as the sum of two squares only if \(p\equiv1\pmod4\).

We would like to prove the other direction, that if \(p\equiv1\pmod4\), then its the sum of two squares. While this turns out to be true, it doesn’t have as simple of a proof 13. First, note that if we have a a number \(d\) s.t. \(d^2\equiv-s^2\pmod p\) for some \(s\), then we know that \(p\) divides \(d^2+s^2\) which looks like a step in the right direction. This motivates the following theorem.

Lemma

If prime \(p\equiv1\pmod4\), then \(-1\equiv\square\pmod p\).

Alternative Pf: Use Wilson's Theorem to show that \((2k)!(2k)!\equiv-1\pmod p\) if \(p=4k+1\). Details left to reader. \(\square\)

Exercise

Show that the converse of this lemma holds as well. If \(-1\equiv\square\pmod p\) for odd prime \(p\), then \(p\equiv1\pmod4\).

Now that we’ve taken that step, we can finally proof the other direction of our previous theorem 14.

Theorem

An odd prime \(p\) can be written as the sum of two squares if \(p\equiv1\pmod4\).

This means that the normal primes that are also Gaussian primes are exactly those that are congruenct to 1 modulo 4. However, are there any Gaussian primes that are not normal primes? Short answer, yes. In fact, if \(p\) is a Guassian prime, then so is \(ip\). Furthermore, it can be shown 15 that \(a+bi\) with \(a,b\neq0\) is a Gaussian prime if and only if \(N(a+bi)\) is a normal prime. Finally, because why stop there, I have one last exercise

Exercise

Extend the work done here to show that an integer \(N\in\mathbb Z\) can be written as the sum of two squares if and only if every prime \(p\equiv3\pmod4\) that divides it does so evenly many times.

As an example, we can write \(180=2^2*3^2*5=6^2+12^2\), but we cannot write \(105=3*5*7\) as the sum of two squares no matter how hard we try.

Thoughts

The second half of this post did not turn out as well as I had hoped it would have. I probably should have thought through the order I would cover steps of the proof, and decided some minimum level of mathematically knowledge that I would assume before writing it in order to avoid it sound like a poorly motivated mess16. But oh well, too late now.

-

I wonder what percentage of my posts start with me thinking back on an ealier time in my life, and if this percentage will remain relativley constant as time passes. ↩

-

This blog is really just a place for me to brag ↩

-

I suspect I was drawn to the consistent combination of brute force, and mathematical sleight of hand I used in answering its questions. I remember starting problems with equations in ~4 variables and then employing some trick to eventually find an answer in all the mess. ↩

-

Except the ones I leave for the reader ↩

-

If you don’t see how this picture is relevant, and don’t want to go to the link, my advice is to find the area of that square two different ways ↩

-

If this fancy Z scares you, don’t let it. It’s just notation for the set of integers so this says a,b,c are integers. The Z is short for some German word, I think but I’d have to look it up to be sure. ↩

-

Have no common factors ↩

-

Technically, we also need to show all (x,y) satisfying x^2+y^2=1 are on the unit circle, but this is easy and essentially the same argument. ↩

-

I spent some time trying to adjust animation speeds so everything was smooth, but then quickly gave up and decided this was good enough ↩

-

Our correspondence isn’t exactly 1-1. No rational number gets matched up with the point reference point (1,0) on the circle. This is fine, and in case you’re curious, it’s a consequence of the fact that our correspondence is continuous and the circle is fundamentally different from the line (Ex. it has a hole while a line does not), but a punctured circle (circle missing 1 point) isn’t (you can uncurl it into a line like we’ve done) ↩

-

If the last footnote makes you think, we still missed (1,0) <—> (1,0,0), this solution comes from m=1 and n=0. This doesn’t contradict the previous footnote, because this choice of m and n gives t=1/0 which is very much not rational. ↩

-

I don’t know the exact details but I saw them once long ago. I’m not going to try to reproduce them here. ↩

-

or at least not one that I know ↩

-

Here, I ignore the issuze of Z[i] being a UFD which means every number factors uniquely into primes like they do in the integers. This is not a trivial/obvious property for a set of numbers to have, but I didn’t want to get into the details of proving this. ↩

-

and is up to you to show that. One direction is easy. The other I’m not 100% sure is true but I’m pretty sure it is. ↩

-

and it being almost circular in the end ↩