About 5ish minutes ago 1, I found this problem, and then started working out a solution on a quarter-piece of paper until I ran out of space. Seemed like the type of thing I might want to blog about, and so I’m going to attempt to finish the solution as I write this post. In case you’re too lazy to click the link, here is the problem, originally tweeted by someone named James Tanton.

Problem

1, 2, 5/2, 17/6, \(\dots\)

Each term is one more than the arithmetic mean of all previous terms. Is there ever again an integer entry?

If you click the link where I found the problem, you will see a blog post where someone generated the first 20 terms of the sequence, and none of them were integers, so at the very least, we’ll need to look at the first 21 terms to know if another integer appears.

Preliminary Results

Despite that last sentence, I did not begin this problem by generating the sequence. I wanted to gain a better understanding of the behavior of the sequence, and my tool of choice for doing that was some algebra. First things first, let’s formally define our sequence and see if that definition leads to any insight2.

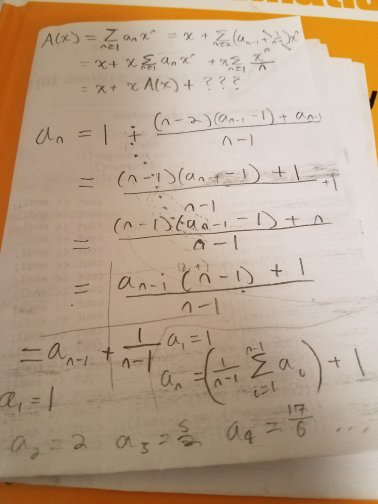

\[\begin{align} a_1 &= 1 \\ a_n &= 1 + \left(\frac1{n-1}\sum_{i=1}^{n-1}a_i\right) & \text{for n}\ge2 \end{align}\]I don’t know about you, but looking at that, I may feel like I have less of a hold on this sequence than before. However, all is not lost. To compute \(a_n\), we need to arithmetic mean of the first \(n-1\) numbers, but to computer \(a_{n-1}\), we needed the arithmetic mean of the first \(n-2\) numbers. Thus, we can compute \(a_n\) directly from \(a_{n-1}\), and there is no need for that ugly sum. This leads to the following, nicer definition of \(a_n\) (for \(n\ge2\)).

\[\begin{align*} a_n &= 1+\frac{(n-2)(a_{n-1}-1)+a_{n-1}}{n-1} \\ &= \frac{(n-1)(a_{n-1}-1)+1}{n-1}+1 \\ &= \frac{(n-1)(a_{n-1}-1)+n}{n-1} \\ &= \frac{a_{n-1}(n-1)+1}{n-1} \\ &= a_{n-1}+\frac1{n-1} \end{align*}\]At this point, I was very surprised by how much simpler this formula was than the previous one. I originally assumed I had made an algebra mistake, and things weren’t this nice, but this formula works for the first 3 or 4 terms, so it must work for all of them, right?

Haven3 convinced myself that I was right, I instantly recognized this as a linear equation. I mean, you start at a some number, and then each step you add a fixed amount to it, so it has to be a line. Unfortunately, I almost as quickly realized that I was completely wrong and that \(\frac1{n-1}\) was not a constant. Still, the equation seemed simple enough to have a nice closed form formula, and that led to the real reason I thought this problem warrented a blog post4…

Generating Functions

I have wanted to talk about generating functions on this blog for a while now, so when I decided to try using them here, I figured it was a good enough excuse to make a post. However, I was in the middle of applying generating functions when I ran out of space, so I do not yet know if this example will actually lead anywhere.

Quickly put, generating functions are a tool in combinatorics for studying recurrence relations using formal power series. Basically, you definie a generating function \(A(x)=\sum\limits_{n\ge1}a_nx^n\), and then you can use the recurrence relation to find a formula for the coefficients for \(A(x)\) which just so happens to give you a formula for \(a_n\). We’re working with formal power series, so we do not worry about issues of convergence. The following lines of algebra mark the end of where I got before starting this post

\[\begin{align*} A(x)=\sum_{n\ge1}a_nx^n &= x + \sum_{n\ge2}\left(a_{n-1}+\frac1{n-1}\right)x^n \\ &= x + x\sum_{n\ge1}a_nx^n + x\sum_{n\ge1}\frac{x^n}n \\ &= x + xA(x) + ??? \end{align*}\]Here, I see two things that could be done5. Either, we can find a closed form formula for that sum (Start with \(\sum_{n\ge1}x^n=\frac x{1-x}\), integrate both sides, and then do some algebra), or we can switch to using exponential generating functions instead. I’ve never used them for anything before - only seen their definition - so that’s what we’re gonna do. We’ll redefine \(A(x):=\sum_{n\ge1}a_n\frac{x^n}{n!}\), and so

\[\begin{align*} A(x)=\sum_{n\ge1}a_n\frac{x^n}{n!} &= x + \sum_{n\ge2}\left(a_{n-1}+\frac1{n-1}\right)\frac{x^n}{n!} \\ &= x + x\sum_{n\ge1}a_n\frac{x^n}{(n+1)!} + \sum_{n\ge1}\frac{x^{n+1}}{n(n+1)!} \end{align*}\]Wow! That is ugly. Welp… I’m not sure why I thought that would be a good idea, but things did not work out as I hoped. Integration it is.

\[\begin{align*} \sum_{n\ge0}x^n &= \frac1{1-x} \\ \int\sum_{n\ge0}x^n\,dx &= \int\frac1{1-x}\,dx \\ \sum_{n\ge0}\frac{x^{n+1}}{n+1} &= -\ln(1-x) \\ \sum_{n\ge1}\frac{x^n}n &= -\ln(1-x) \end{align*}\]This allows us to solve for (the original) \(A(x)\)

\[\begin{align*} A(x) &= x + xA(x) - x\ln(1-x) \\ A(x) &= \frac{x-x\ln(1-x)}{1-x} \end{align*}\]This actually has a nice look to it. Unfortunately, it does not have a nice, simple look to it. Now that we have a generating function, we find its power series in order to get a formula for \(a_n\) 6.

\[\begin{align*} A(x) &= \frac x{1-x} - \frac x{1-x}\ln(1-x)\\ &= \sum_{n\ge1}x^n + \left(\sum_{k\ge1}x^k\right)\left(\sum_{m\ge1}\frac{x^m}m\right)\\ &= \sum_{n\ge1}x^n + \sum_{n\ge1}\sum_{\substack{k+m=n\\k,m\ge1}}\frac{x^{k+m}}m\\ &= \sum_{n\ge1}x^n + \sum_{n\ge1}\left(\sum_{m=1}^{n-1}\frac{x^n}m\right)\\ &= \sum_{n\ge1}x^n + \sum_{n\ge1}H_{n-1}x^n\\ &= \sum_{n\ge1}\left(1+H_{n-1}\right)x^n \end{align*}\]Above, \(H_n\) is the \(n\)th harmonic number \(H_n=\sum_{k=1}^n\frac1k\) and \(H_0=0\). Finally, this gives us the surprising result that \(a_n=1+H_{n-1}\) for all \(n\ge1\). Returning to our original question, we were interested in whether or not \(a_n\) is an integer for any \(n>2\). From this formula, we see that this is equivalent to asking whether \(H_n\) is an integer for any \(n\ge2\).

Off the top of my head, I do not know the answer to this, but my gut tells me that it is no. A bit of reflection showed me no way to prove this, so I did the only rational thing, and got on Wikipedia. According to Wikipedia, Bertrand’s postulate implies that \(H_n\) is not an integer for \(n\ge2\).

Conclusion

For completeness, I’ll state Bertrand’s postulate here.

Bertrand’s Postulate

For any integer \(n>3\), there exists at least one prime \(p\) with \(n<p<2n-2\).

If you do not immediately see how this implies that 1 is the only harmonic integer (\(H_0=0\) is what I defined to keep the formula simple. 0 is not considered a harmonic number), then you are not alone. I don’t see it either, but this post won’t end without me figuring something out and explaining it 7. In the meantime, here’s the paper where it all started

After \(\approx45\) minutes of thinking about it and getting nowhere, I finally had an epiphany.

Theorem

Fix any \(n>1\). Then, \(H_n\) is not an integer.

So, assuming Bertrand’s Postulate, we have our answer, and have shown it rigouously correct. If not having proved the postulate bothers you, then luckily for you, my epiphany showed me more elementary proofs of the above theorem as well.

-

I don’t remember how long ago it actually was, but it was almost certainly more than just 5. ↩

-

I had thought about starting with a_0=0, since 1 more than the arithmetic mean of {0} is 1, and so the sequence would proceed correctly, but this was only after I had written down this definition, and I did not want to have to erase and rewrite it, so we’re stuck with it. ↩

-

Is this even a word? ↩

-

While typing this, the idea to try using induction to prove the claim crossed my mind. I haven’t thought about it seriously enough to know if it’s viable, but I’m still recounting the work I’ve done so far, and I did not attempt induction in the minutes leading up to this post, so generating functions it is. ↩

-

Besides induction. That avenue is not getting explored for a while, or ever. We’ll see ↩

-

I’d just like to say, there is almost certainly an easier way to solve the original problem, and it’s still too early to say for sure that this will be helpful. ↩

-

Remember when I said there was almost certainly an easier way to do this? Looking back at the recurrence relation from the first section, it should have been fairly obvious that a_n=H_{n-1}+1. The recurrence screams harmonic numbers, and the +1 is just so a_1=1 ↩