I recently decided to try to solve all of the Expert Unblock Me puzzles. After solving around 20 or so puzzles, I realized that I did not have the time to solve them all 1. I didn’t want to simply give up since I had just started the challenge, so I decided to modify my original goal. Instead of swiping myself through the remaining nearly 800 puzzles, I would just write a program to find solutions for me. By doing this, I will have basically solved all of them.

The Idea

My plan was to find solutions to the puzzle using a standard graph traversal algorithm like A* 2. The program would keep track of several potential solutions to a puzzle at once, and explore the ones that look the most promising. Using A* as opposed to something like depth-first search would guarantee that the solution found in the end was optimal without being much more complicated to implement, so it seemed like an obvious search.

The First Step

Before I started writing the program, I needed to get some puzzles that I could test it on. I figured the puzzle were probably available online somewhere, so my plan was to just download all of them. After a quick google search, I learned that you couldn’t simply download all Unblock Me puzzles 3; they just weren’t available. Unblock Me isn’t an extremely complicated game, so I could always have just made my own puzzles, but that sounded like a lot of work, so I need to think of something else. Thankfully, I wasn’t the first person to write a program like this, so I decided to see what my predecessors had done. In most of the examples I saw, the creator had made their own project, but one person had his program load puzzles in from images. This sounded promising.

From Pixels to Puzzles

A quick glance of the blog post by the guy who loaded puzzles from images revealed that his implementation only worked on screenshots from his iPhone 4. In his program, he had hardcoded the locations of the tile centers, and so could look at the pixels at these locations to figure where all the blocks were, and where there was just empty space. I didn’t like that this approach was restricted to images from a specific source, so I decided to come up with my own method for constructing puzzles from images.

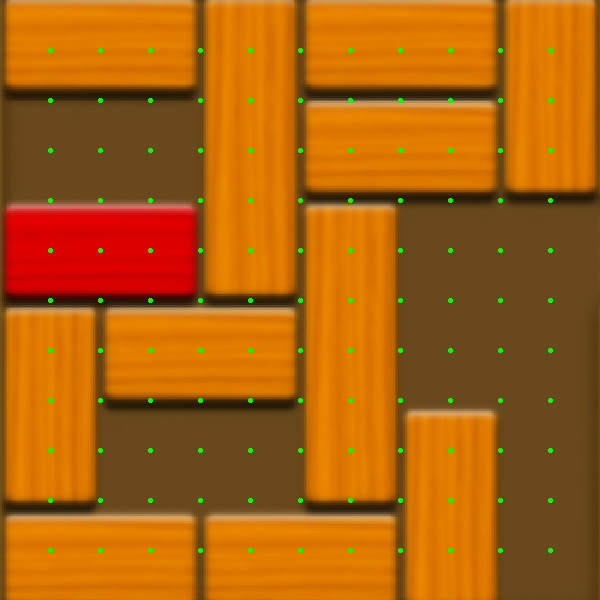

The basic idea is simple. First, the program figures out what region of the image the game takes place in 5. It then crops the image to just that region and resizes it to be 600 x 600. At this point, all that’s left is the part of the image that matters, so since we know what size the picture is, we can hard code the potential locations of tiles and boarders. At this point, the program samples the pixels where the tile centers and tile boarders could be to determine the layout of the puzzle. By first detecting the region of the image where the game lies, the program is able to load puzzles from image less nice than screenshots.

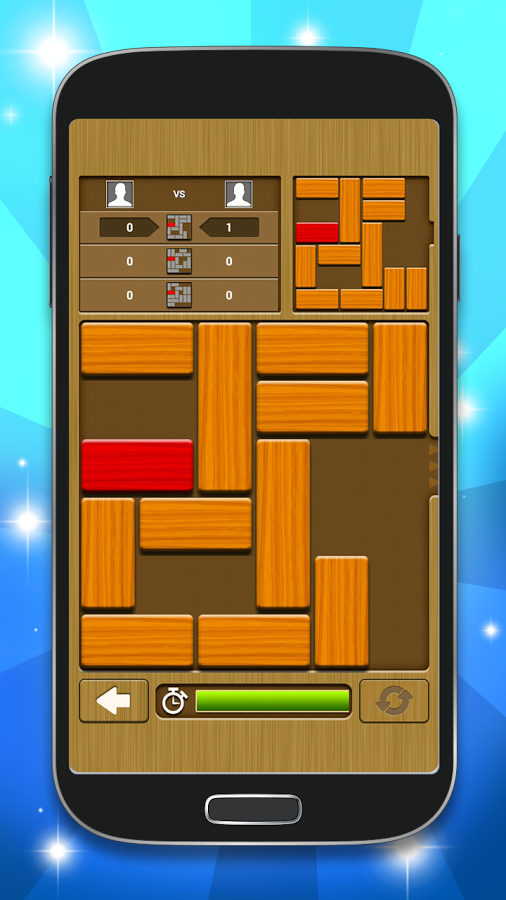

Left: The original image. Right: The game region detected.

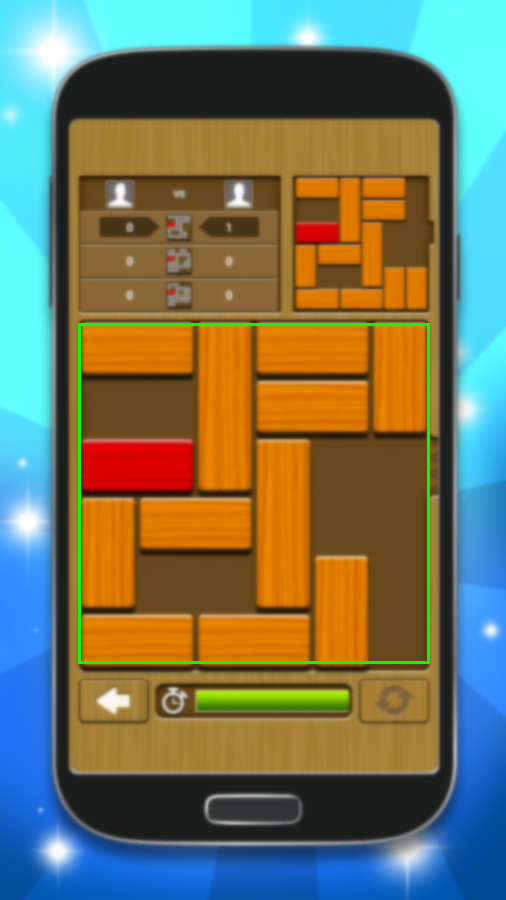

Left: The image after being cropped and resized. Right: The points the program uses to check for tiles and boarders.

Region Detection

The most interesting part of detecting a puzzle in an image, is the first step. This is done in a bit of an ad hoc manner, and so is still not perfect 6. The program assumes the correct region is located in a square in the image, and so tries to find its top-left and bottom-right corners. It does this by finding bounds on the region in the x- and y-axes, respectively. The beginning of the region is generally darker than rest of the image, so it starts by looking for dark, horizontal lines. Once it has found one, it assumes this is the top of the region and tries to find the left and right sides of the region 7. Once it has the top figured out as well as the left and right sides, it looks for lines containing blocks and for blank lines. Every time it finds one, it sets it as the bottom of the region. By the time its left the true region, there are no more of either type of line 8, so we don’t worry about false positives.

The whole procedure takes 5 functions and ~80 lines of (C++) code 9.

bool line_contains_blocks(const CImg<unsigned char>& red_channel) {

auto red_count = std::count_if(red_channel.begin(), red_channel.end(), [](auto red) {

return red >= 200;

});

return red_count >= .26*red_channel.width();

}

bool line_is_blank(const CImg<unsigned char>& red_channel, const CImg<unsigned char>& green_channel, const CImg<unsigned char>& blue_channel) {

const int threshold = .88*red_channel.width();

auto red_count = std::count_if(red_channel.begin(), red_channel.end(), [](auto red) {

return 90 <= red && red <= 110;

});

auto green_count = std::count_if(green_channel.begin(), green_channel.end(), [](auto green) {

return 50 <= green && green <= 80;

});

auto blue_count = std::count_if(blue_channel.begin(), blue_channel.end(), [](auto blue) {

return blue <= 40;

});

return red_count >= threshold && blue_count >= threshold && green_count >= threshold;

}

bool line_is_edge(const CImg<unsigned char>& red_channel, const CImg<unsigned char>& green_channel, const CImg<unsigned char>& blue_channel) {

const int threshold = .88*red_channel.width();

auto red_count = std::count_if(red_channel.begin(), red_channel.end(), [](auto red) {

return red <= 80;

});

auto green_count = std::count_if(green_channel.begin(), green_channel.end(), [](auto green) {

return green <= 60;

});

auto blue_count = std::count_if(blue_channel.begin(), blue_channel.end(), [](auto blue) {

return blue <= 40;

});

return red_count >= threshold && blue_count >= threshold && green_count >= threshold;

}

std::tuple<int, int> get_x_bounds(const CImg<unsigned char>& img, int y) {

int x_start = -1, x_end = img.width()-1;

for (size_t column = 0; column < img.width(); ++column) {

int red = img(column, y, 0, 0);

int green = img(column, y, 0, 1);

int blue = img(column, y, 0, 2);

if (red + green + blue < 220) {

if (x_start == -1) {

int nearby_red = img(std::max<int>(column, 5)-5, y, 0, 0);

x_start = nearby_red > 150 ? column : x_start;

} else {

int nearby_red = img(std::max<int>(column, 5)+5, y, 0, 0);

int nearby_blue = img(std::max<int>(column, 5)+5, y, 0, 2);

x_end = (nearby_red >= 150 && nearby_blue < 30) || (nearby_blue < 70 && nearby_red >= 100) ? column : x_end;

}

}

}

return std::make_tuple(x_start, x_end);

}

std::tuple<int, int, int, int> get_game_region(const CImg<unsigned char>& img) {

int x_start = -1, x_end = img.width()-1;

int y_start = -1, y_end = img.height()-1;

for (size_t line = 0; line < img.height(); ++line) {

auto red_channel = img.get_crop(x_start, line, 0, 0, x_end, line, 0, 0);

auto green_channel = img.get_crop(x_start, line, 0, 1, x_end, line, 0, 1);

auto blue_channel = img.get_crop(x_start, line, 0, 2, x_end, line, 0, 2);

if (line_is_edge(red_channel, green_channel, blue_channel) && line - y_start < img.height()/3) {

y_start = line;

std::tie(x_start, x_end) = get_x_bounds(img, line);

} else if (line_contains_blocks(red_channel) || line_is_blank(red_channel, green_channel, blue_channel)) {

if (y_start == -1) {

y_start = line;

std::tie(x_start, x_end) = get_x_bounds(img, line);

} else {

y_end = line;

}

}

}

std::tie(x_start, x_end) = get_x_bounds(img, (y_start+3*y_end)/4);

x_start = std::max(x_start, 0);

y_start = std::max(y_start, 0);

return std::make_tuple(x_start, y_start, x_end, y_end);

}

The Rest of the Program

Fining the tile layout is less interesting. Pixel values at the green points in the above image tell you whether a location on the board is a tile, empty, or the boarder between two tiles 10. This information lets you reconstruct the scene. After that, A* gives you the shortest solution, and you’re done.

A Confession

I said that the program used A* search to find the solution, and while this is technically true, it is also misleading. A* search makes use of a heuristic 11 to determine how promising a potential solution is, and always explore the most promising solution 12. However, if you look at the code for this program, you will see a line that looks like this:

int Solver::heuristic(const Puzzle& p) {

return 0;

}

so the program isn’t actually using a (helpful) heuristic at all 13. This means that it’s really performing a greedy best-first search and not (strictly) A* search, except that’s not the end of the story. The measure of goodness for a solution used by the program is the number of moves it takes, its length. That means the program always explores the potential solution with the shortest length which means that its actually performing a breadth-first search and not (strictly) best-first search 14. The program is coded as if its performing A* search even though its really doing breadth-first search, so it is less effecient than it could be 15.

Final Thoughts

This was a fun little project. It started out as a means to solve puzzles, but looking back, the best part of it was writing the code to detect the game region. This was a fun task because there wasn’t an obvious solution when I started, and the solution I came up with was motivated/justified by exploring (looking at different pictures, testing different potential solutions, etc.). Multiplie times, I would get something working only to have it fail on the next image I tested it on, and have to adapt/replace it. In the end, I think what I have is adequate although far from perfect. One possibility that would be interesting to explore is training a neural network to detect the game region 16. The biggest issue I see with something like this is having to label who knows how many images of puzzle for the net to perform really well, although this issue can be somewhat alleviated by using something like Tensorflow for Poets.

-

or the skill. Every few puzzles, I’d get stuck and just start swiping randomly until I got in a position that look helpful. ↩

-

Pronounced “A-star” ↩

-

To make things worse, you couldn’t even do something more reasonable like download 100 of them. ↩

-

I did not read through the whole post, so I could be wrong about this ↩

-

It ignores the score, level, etc. and focusses in on the blocks ↩

-

That is especially annoying because the rest of the process is very sensitive to this part. The tile/boarder locations are hardcoded so if the detected region is a little off, the wrong pixels are sampled and the produced puzzle is does not match the picture, and is likely invalid (red block in an illegal position, overlapping blocks, etc.) ↩

-

The image is processed one line at a time from top to bottem. If a second dark, horizontal line is found, it changes this line to be the top of the region unless it has already reached low in the image (this is because there are usually other dark lines before the true top, but not many after the true top). ↩

-

hopefully ↩

-

plus a few magic numbers and zero comments ↩

-

or between a tile and an empty space ↩

-

a function that takes in a puzzle and returns a lower bound on how many moves it is away from being solved. ↩

-

the solution with lowest sum of number of steps made so far and estimated number of remaining steps ↩

-

originally, it was, but the one it used sometimes overestimated the number of steps left so the solutions it found were not guaranteed to be optimal. ↩

-

That last sentence may make it seem like there’s no difference between best-first and breadth-first search in general. Imagine you were looking for the shortest path between two cities. Breadth-first would focus on paths with short lengths (number of intermediate cities), while best-first would focus on paths with short distances (total miles travelled on path). These two ideas coincide in Unblock Me where length is a good measure of distance, but they do not always. ↩

-

oops ↩

-

You could use a conv net with four outputs, the percentage along the {x, y}-axis for the {top-left, bottom-right} corner ↩