For a long time I’ve been telling myself that I should try and get a solid understanding of characteristic classes, so why not do that now?

Before getting into things, as usual, a few remarks about this post. First, by a “characteristic class” I mean a functorial way of attaching a cohomology class to a vector bundle 1. There are many of these, but because I care more about algebraic/holomorphic things than I do about smooth things, we will basically just look at Chern classes. I want to be quite detailed in this post, so even just focusing on these will require a lot of work. On the upside, the payoff will be a good amount of interesting/neat applications/calculations. Second, I’m going to try 2 to make this post be a good one 3. I feel like many of my recent posts have either been overall meh or have started off good only for me to fumble the ending, and this is starting to really bother me. Hence, for this post, I’m going to try to prioritize quality/detail 4 over “just producing a finished product” and see how this feels. Third, this post is titled “Characteristic Classes” but, if possible, I’d like to throw in a few things not strictly related to/requiring characteristic classes, but which are both at least somewhat related to them and things I’ve been wanting to improve my understanding of. Finally, characteristic classes are one of those things that can be constructed a dozen different ways, and can be given a million different treatments. Throughout this post, I’ll try to maintain an unapologetically algebro-topological perspective, so don’t expect me to e.g. say the words “connection” or “integration” 5. $ \newcommand{\CW}{\mathrm{CW}} \newcommand{\Top}{\mathrm{Top}} \newcommand{\Set}{\mathrm{Set}} \newcommand{\Grp}{\mathrm{Grp}} \DeclareMathOperator{\Ho}{Ho} $

Throughout this post, assume the base space of any fibre bundle is Hausdorff and paracompact, so a CW complex or a manifold or a metric space or something like this. 6 In particular, base spaces will always admit partitions of unity.

Principal $G$-Bundles

The key example of a characteristic class to keep in mind throughout this post is the first Chern class $c_1(E)$ of a complex (topological) line bundle $E\to X$ which was introduced at the end of the post on Brown Representability. This class lives in $X$’s second integral cohomology and actually completely characterizes $E$ up to isomorphism (as a topological, complex line bundle over $X$). We constructed this class as the pullback on the canonical generator $\gamma\in\hom^2(\CP^\infty;\Z)\simeq\Z\gamma$ of the cohomology of $\CP^\infty$ along $E$’s classifying map $X\to BS^1\simeq\CP^\infty$ 7. Motivated by this, in order to define cohomology classes for higher rank (complex) vector bundles, we will want to understand the cohomology of $BU(n)$ for all $n$ 8.

Before calculating $\ast\hom(BU(n);\Z)$, I want to patch up a hole in my introduction to Principal $G$-bundles from the Brown Representability post. In particular, I claimed that such bundles satisfy a homotopy invariance property, but did not proof this. This fact is high-key the starting point to being able to use $G$-bundles productively in homotopy theory, so this is probably actually something worth writing down a proof of. First recall the definition of a principal $G$-bundle.

In order to show that homotopic maps induce isomorphic pullback bundles, the following lemma will be useful. In short, it says that $G$-bundle maps lying above the identity are automatically isomorphisms.

(Surjectivity) We now treat surjectivity. Fix some $p'\in P'$ lying over $b\in B$. Let $p\in P$ be any point which also lies over $b$, so $\phi(p)$ and $p'$ belong to the same fiber of $P'$. Hence, by transitivity of the $G$-action, there is some $g\in G$ such that $\phi(p)\cdot g=p'$, and so $p\cdot g\in P$ is a preimage of $p'\in P'$.

(Continuity of $\inv\phi$) Now that we know $\phi$ is bijective, all that remains is to show that it is an open mapping. For this, we work locally. Pick some small open $U\subset B$ such that we have local trivializations $P\vert_U\simeq U\by G$ and $P'\vert_U\simeq U\by G$. Then, in local coordinates, $\phi\vert_U$ must take the form $$\phi:(b,g)\mapsto\parens{b,\phi'(b,g)}=\parens{b,\phi'(b,e)g}$$ for some $\phi':U\by G\to G$ satisfying $\phi'(b,gh)=\phi'(b,g)h$. Thus, $\inv\phi$ is of the form $$(b,g)\mapsto(b,\inv{\phi'(b,e)}g)$$ which is visibly continuous.

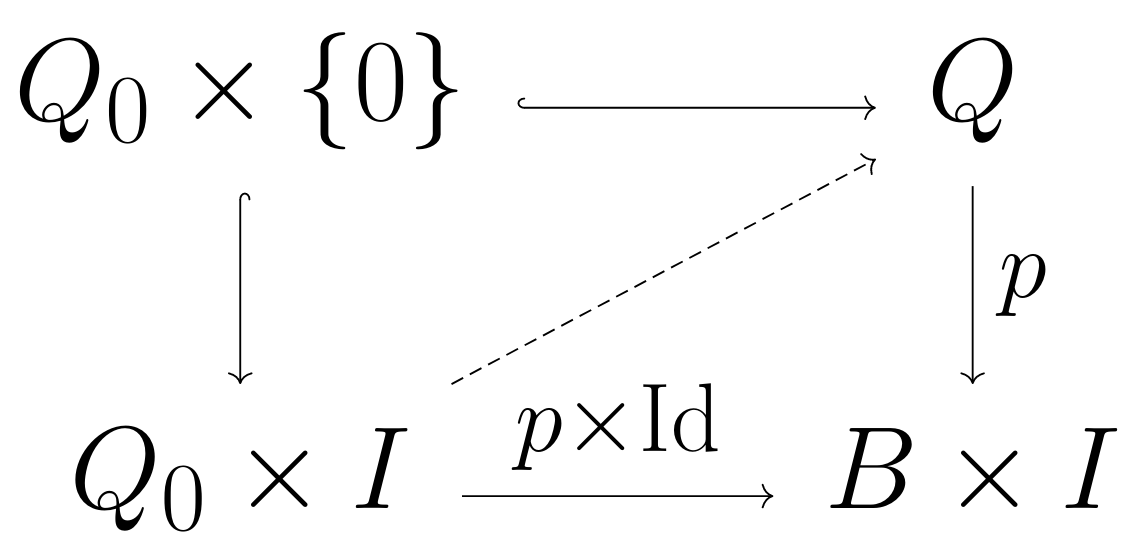

We seek an isomorphism $Q_0\by I\iso Q$ (lying over the identity on the base). Note that this amounts to extending the canonical map $Q_0\by\{0\}\iso Q_0\into Q$ into one from $Q_0\by I\to Q$. In other words, we are attempting to solve the following lifting problem.

With that taken care of, let’s return to our goal of understanding characteristic classes. As was noted earlier, the first step in doing so is determining the cohomology (ring) of $BU(n)$ since this space classifies principal $U(n)$-bundles and so classifies rank $n$ complex vector bundles. We will spend a section going over a technical tool useful for performing this calculation (and also useful for proving things about characteristic classes in general), and then after that we will get our cohomology classes.

Splitting Principle

Our first major goal is to show that

\[\ast\hom(BU(n);\Z)\simeq\Z[c_1,c_2,\dots,c_n]\text{ where }c_i\in\hom^{2i}(BU(n);\Z),\]and so obtain $n$ different characteristic classes for any rank $n$ vector bundle, the Chern classes. In order to do this, we will carry out an inductive argument, relating the cohomology of $BU(n)$ to that of $BU(n-1)\by BU(1)$. This argument will make use of a general construction that allows one to peel of a single (line bundle) summand from an arbitrary vector bundle.

To see what I mean, let $p:E\to B$ be any rank $n+1$ vector bundle. Implicitly cover $B$ by opens $U_i\subset B$ on which $p$ trivializes, and let $\tau_{ij}:U_i\cap U_j\to U(n+1)\subset\GL_{n+1}(\C)$ be $p$’s transition functions 9. Then, we can projectivize $E$ in order to form a $\CP^n$-bundle $\pi:\P(E)\to B$ whose fibers are $\inv\pi(b)\simeq\P(\inv p(b))=\P(E_b)$ (I use $E_b$ to denote $E$’s fiber over $b\in B$), and whose transition functions are the compositions

\[U_i\cap U_j\xto{\tau_{ij}}U(n+1)\into\GL_{n+1}\C\onto\PGL_n\C.\]This space $\P(E)$, called projectivization of $E$ is where we will peel off a summand of $E$. A point $x\in\P(E)$ belongs to the projective space $\P(E)_ {\pi(x)}=\P(E_{\pi(x)})$ and so is identifiable with a line in the fiber $E_{\pi(x)}=\inv p(\pi(x))$. Note that $E$ has a few natural vector bundles. First, there is the pullback bundle $\pull\pi E\to\P(E)$ whose fiber above a point $x\in\P(E)$ is the fiber $E_{\pi(x)}$ of $E\xto pB$ above $\pi(x)\in B$. Inside of $\pull\pi E$, one can find the tautological subbundle

\[L_E:=\bracks{(\l, v)\in\P(E)\by E:v\in\l}\subset\pull\pi E\]whose fiber above a point $\l\in\P(E)$ is the line $\l\subset E_{\pi(\l)}$ it corresponds to. The tautological quotient bundle $Q_E$ on $\P(E)$ is defined by its place in the following exact sequence:

\[0\too L_E\too\pull\pi E\too Q_E\too0.\]Note that if we restrict the above sequence to the fiber $\P(E)_ b=\P(E_b)$ above any point $b\in B$, then we recover the normal sequence of tautological bundles on projective space 10. The existence of this sequence allows us to write $\pull\pi E\simeq L_E\oplus Q_E$ as the sum of a line bundle and a rank $n$ vector bundle.

- $L,E,Q$ all three trivialize over $U_i$, i.e. $L\vert_{U_i}\simeq U_i\by\C^m$, $E\vert_{U_i}\simeq U_i\by\C^n$, and $Q\vert_{U_i}\simeq U_i\by\C^k$.

- There exists a partition of unity $\rho_i:B\to[0,1]$ subordinate to the $U_i$'s. That is, $\supp\rho_i\subset U_i$ for all $i$ (the cover $\{U_i\}$ assumed locally finite) and $$\sum_i\rho_i(x)=1$$ for all $x\in X$ (all but finitely many terms above are $0$).

The above lemma justifies our earlier claim that $\pull\pi E\simeq L_E\oplus Q_E$.

In order to carry out our induction argument, we still need to be able to relate the cohomology of $\P(E)$ to that of $E$ (e.g. cohomology of $BU(n-1)\by BU(1)$ to that of $BU(n)$ by the exercise above). We do this now. First recall the tautological exact sequence

\[0\too L_E\too\pull\pi E\too Q_E\too0\]on $\P(E)$, and let $x=c_1(\dual L_E)\in\hom^2(\P(E);\Z)$ ($\dual L_E$ is the dual line bundle). As earlier remarked, this sequence restricts to the normal tautological exact sequence on the fibers $\P(E)_ b\simeq\P^n$; in particular, $L_E\vert_{\P(E)_ b}$ is the usual tautological line bundle 11, and so the canonical generator for $\hom^2(\P(E)_ b;\Z)$ is precisely $x\vert_{\P(E)_ b}$ (this is the reason for taking the dual of $L_E$ before). Taking self cup-products, this means that ${1,x,x^2,\dots,x^{n-1},x^n}\subset\ast\hom(\P(E);\Z)$ are global cohomology classes whose restriction to each fiber $P(E)_ b=\P(E_b)\simeq\P^n$ freely generate the cohomology there (as a module). This allows us to determine the cohomology of $\P(E)$ via the following generalization of the Kunneth formula.

This means we are justified in forming the Serre spectral sequence $$E_2^{p,q}=\hom^p(B;\hom^q(F;R))\implies\hom^{p+q}(E;R).$$ By assumption, $\hom^q(F;R)$ is a free $R$-module (i.e. of the form $R^{\oplus k}$ for some $k$, depending on $q$), so we see immediately that $$E_2^{p,q}=\hom^p(B;\hom^q(F;R))\simeq\hom^p(B;R)\otimes_R\hom^q(F;R)\simeq E_2^{p,0}\otimes_RE_2^{0,q}.$$ Recall the the differential $d_2$ on the $E_2$-page has bidegree $(2,-1)$, i.e. we have $$d_2:E_2^{p,q}\simeq E_2^{p,0}\otimes_RE_2^{0,q}\to E_2^{p+2,0}\otimes_RE_2^{0,q-1}\simeq E_2^{p+2,q-1}.$$ By the Leibniz rule, for $a\in E_2^{p,0}$ and $b\in E_2^{0,q}$, we have $$d_2(a\otimes b)=(a\otimes1)d_2(1\otimes b)+(-1)^p(1\otimes b)d_2(a\otimes 1)=(a\otimes1)d_2(1\otimes b)$$ since $d_2(a\otimes 1)\in E_2^{p+2,-1}=0$. At the same time, $E_\infty^{0,q}=G^0\hom^q(E;R)=\hom^q(E;R)/F^1\hom^q(E;R)$ where $F^1\hom^q(E;R)=\ker(\hom^q(E;R)\to\hom^q(E_0;R))$ where $E_0=F$. In other words, $$E_\infty^{0,q}\simeq\im(\hom^q(E;R)\to\hom^q(F;R))=\hom^q(F;R)\simeq E_2^{0,q},$$ from which we see that $d_2(b)=0$ for all $b\in E_2^{0,q}$ (so $E_2^{0,q}$ survives to the $E_\infty$-page). Thus, $d_2=0$ in all degrees, so the $E_2$-page is the $E_\infty$-page! This is almost enough for us to conclude that $$\hom^n(E;R)\simeq\bigoplus_{p+q=n}E_\infty^{p,q}=\bigoplus_{p+q=n}E_2^{p,q}\simeq\bigoplus_{p+q=n}\hom^p(B;R)\otimes_R\hom^q(F;R)$$ which would exactly give the claim. In orer to actually conclude this claim, recall that $E_\infty^{p,q}\simeq G^p\hom^{p+q}(E;R)$ are successive quotients in a filtration $$0\subset F^{p+q}\hom^{p+q}(E;R)\subset F^{p+q-1}\hom^{p+q}(E;R)\subset\dots\subset F^0\hom^{p+q}(E;R)=\hom^{p+q}(E;R).$$ of $\hom^{p+q}(E;R)$. In particular, we have exact sequences $$0\too F^{k+1}\hom^n(E;R)\too F^k\hom^n(E;R)\too E_\infty^{k,n-k}\too0.$$ Since $E_{\infty}^{k,n-k}\simeq\hom^k(B;R)\otimes_R\hom^{n-k}(F;R)$, the above sequence splits via the map $\sigma:E_\infty^{k,n-k}\to F^k\hom^n(E;R)$ given by $\sigma(\alpha\otimes\beta)=\pull\pi(\alpha)s(\beta)$ (i.e. $\sigma=f\vert_{E_\infty^{k,n-k}})$, and so $$F^k\hom^n(E;R)\simeq F^{k+1}\hom^n(E;R)\oplus E_\infty^{k,n-k}.$$ Since this holds for all $k$ and $F^{n+1}\hom^n(E;R)=0$, induction shows that indeed $$\hom^n(E;R)\simeq\bigoplus_{p+q=n}E_\infty^{p,q}=\bigoplus_{p+q=n}E_2^{p,q}\simeq\bigoplus_{p+q=n}\hom^p(B;R)\otimes_R\hom^q(F;R),$$ so we win.

Returning to our situation of interest, we have a projective bundle $\P(E)\xto\pi B$ with tautological exact sequence

\[0\too L_E\too\pull\pi E\too Q_E\too0.\]We observed that, letting $x=c_1(\dual L_E)$, the set ${1,x,x^2,\dots,x^{n-1},x^n}\subset\ast\hom(\P(E);\Z)$ freely generates the cohomology of each fiber. Thus, by Leray-Hirsch, $\ast\hom(\P(E);\Z)$ is a free $\ast\hom(B;\Z)$-module with basis $1,x,x^2,\dots,x^{n-1},x^n$. Thus 12, there must exist some polynomial $p(x)\in\ast\hom(B;\Z)[x]$, say (recall $n+1=\rank E$)

\[p(x)=x^{n+1}+c_1(E)x^n+\dots+c_n(E)x+c_{n+1}(E)\]such that $\ast\hom(\P(E);\Z)\simeq\ast\hom(B;\Z)[x]/(p(x))$. For now, just think of $c_i(E)\in\hom^{2i}(B;\Z)$ above as notation for the coefficient in this polynomial 13. In particular, we have an injection $\ast\hom(B;\Z)\into\ast\hom(\P(E);\Z)$. This gives our link between the cohomology of $B$ and that of $\P(E)$. We saw earlier that if we take $B=BU(n)$ and $E=EU(n)$ (modulo the distinction between a vector bundle and a $U(n)$-bundle), then $\P(E)\simeq BU(n-1)\by BU(1)$, so we are ready to carry out our induction argument.

This phenomenon can be described universally. Let $f:(BU(1))^n\to BU(n)$ be the classifying map for the sum of $n$ copies of the universal line bundle (i.e. the classifying map for the universal sum of $n$ line bundles), and consider any rank $n$ vector bundle $E\to B$. This is pulled back along some classifying map $g:B\to BU(n)$, so we can form the pullback $B'=B\by_{BU(n)}BU(1)^n$. $$\begin{CD} B' @>h>> B\\ @Vg'VV @VVgV\\ BU(1)^n @>>f> BU(n) \end{CD}$$ By construction, the pullback bundle $E'=\pull hE\to B'$ has $g\circ h=f\circ g':B'\to BU(n)$ as its classifying map. Since this map factors through $BU(1)^n$, we see that $E'$ splits as the sum of $n$ line bundles, so we can observe this splitting phenomenon without needing any construction. However, this perspective has the downside that it is potentially harder to see that $B$'s cohomology injects into that of $B'$. This is needed, for example, if you want to reduced proofs of properties of Chern classes of general vector bundles to the case of sums of line bundles.

Cohomology of $BU(n)$

Recall that $BU(1)\simeq\CP^\infty$ and so its cohomology ring is $\ast\hom(BU(1);\Z)\simeq\Z[c_1]$ with $c_1\in\hom^2(BU(1);\Z)$ the first Chern class. Also, from the previous section, recall that we have ring isomorphisms

\[\ast\hom(BU(n-1)\by BU(1);\Z)\simeq\ast\hom(BU(n);\Z)[x]/(p_n(x))\]where $\deg x=2$ (i.e $x\in\hom^2(BU(n-1)\by BU(1);\Z)$) and

\[p_n(x)=x^n+c_1(EU(n))x^{n-1}+\dots+c_{n-1}(EU(n))x+c_n(E)\in\ast\hom(BU(n);\Z)[x]\]is some polynomial 14. Our goal this section is to prove the following.

We already know this in the case $n=1$. Let’s see how the argument goes for $n=2$. Here, using Kunneth on the left, we have

\[\Z[c_1,c_1']\simeq\ast\hom(BU(1)\by BU(1);\Z)\simeq\ast\hom(BU(2);\Z)[x]\left./\parens{x^2+c_1(EU(2))x+c_2(EU(2))}\right.\]with $\deg c_1=\deg c_1’=2=\deg x$. Now, the fibration $\pi:BU(1)\by BU(1)\to BU(2)$ we are using pulls the universal rank $2$ vector bundle $EU(2)$ into a sum $EU(1)\oplus EU(1)$ of two copies of the universal line bundle 15. Thus, recalling how we defined $x$ earlier, we see that we can take $x=-c_1\in\hom^2(BU(1);\Z)$ above. That is, $c_1^2-c_1(EU(2))c_1+c_2(EU(2))=0$. Similarly, by symmetry (e.g. the automorphism $BU(1)\by BU(1)\iso BU(1)\by BU(1)$ permuting the factors), we equally see that $(c_1’)^2-c_1(EU(2))c_1’+c_2(EU(2))=0$. In other words,

\[x^2+c_1(EU(2))x+c_2(EU(2))=(x+c_1)(x+c_1')=x^2+(c_1+c_2')x+c_1c_1'\]as polynomials. Matching coefficients, we see that $c_1(EU(2))=c_1+c_1’$ and $c_2(EU(2))=c_1c_1’$ are given by the elementary symmetric polynomials in $c_1,c_1’$. Thus, by Galois theory 16, $\Z[c_1(EU(2)),c_2(EU(2))]$ gives a polynomial algebra in $\ast\hom(BU(2);\Z)$. We claim this is the whole thing. This follows from a counting argument. We know, from Leray-Hirsch, that

\[\Z[c_1,c_1']\simeq\ast\hom(BU(2);\Z)\otimes\ast\hom(\P^1;\Z)\]additively (i.e. as graded modules). So, letting $S_k$ denote the degree-$k$ part of a graded ring $S$, (cohomology in odd degrees vanishes)

\[\begin{align*} k+1 &=\rank_\Z\Z[c_1,c_1']_ {2k}\\ &=\rank_\Z\parens{\ast\hom(BU(2);\Z)\otimes\ast\hom(\P^1;\Z)}_ {2k}\\ &=\rank_\Z\hom^{2k}(BU(2);\Z)+\rank_\Z\hom^{2k-2}(BU(2);\Z)\\ &\ge\rank_\Z\Z[c_1(EU(2)),c_2(EU(2))]_{2k}+\rank_\Z\Z[c_1(EU(2)),c_2(EU(2))]_{2k-2}\\ &=\parens{\floor{\frac k2}+1}+\parens{\floor{\frac{k-1}2}+1}\\ &=k+1. \end{align*}\]This shows that $\Z[c_1(EU(2)),c_2(EU(2))]_ n=\hom^n(BU(2);\Z)$ for all $n$, so

\[\ast\hom(BU(2);\Z)\simeq\Z[c_1,c_2]\]with $c_1=c_1(EU(2))$ and $c_2=c_2(EU(2))$ as desired!

We now handle the general case $n\ge2$. Based on how the $n=2$ case played out, let’s update our goal.

Chern Classes

With the conclusion of the previous section, we have obtained our Chern classes, canonical generators of the cohomology ring $\ast\hom(BU(n);\Z)\simeq\Z[c_1,c_2,\dots,c_n]$. In this section, we will collect a few basic properties of these classes. First, for visibility’s sake, let’s throw in a definition block.

- They are functorial, i.e. $\pull fc_i(E)=c_i(\pull fE)$ always.

- They vanish in large degree, i.e. $c_i(E)=0$ if $i>\rank_\C(E)$.

- They vanish for trivial bundles, i.e. $c_i(B\otimes\C^n)=0$ unless $i=0$.

- They satisfy a product formula, i.e. $c(E\oplus F)=c(E)c(F)$.

- If $E$ is the tautological line bundle on $\CP^n$, then $c_1(E)\in\hom^2(\CP^n;\Z)$ is a generator.

We also want to show that $c_1(L\otimes L’)=c_1(L)+c_1(L’)$ when $L,L’$ are both line bundles. For this, recall 17 that $BU(1)\simeq\CP^\infty$ also represents second integral cohomology. That is, we have natural isomorphisms (of functors)

\[\hom^2(-;\Z)\simeq[-,\CP^\infty]\simeq B(-)\]where $[X,\CP^\infty]$ is the set of homotopy classes of maps from $X\to\CP^\infty$ and $B(X)$ is the set of isomorphism classes of principal $U(1)$-bundles. Note that $\hom^2(-;\Z)$ is a functor $\Ho(\push\CW)\to\Ab$; that is, it spits about abelian groups, not just sets. As such, we have an “addition natural transformation” $m:\hom^2(-;\Z)\by\hom^2(-;\Z)\to\hom^2(-;\Z)$ such that, for any $X\in\Ho(\push\CW)$ (say $X$ a topological space with the homotopy type of a CW complex 18)

\[m_X:\hom^2(X;\Z)\by\hom^2(X;\Z)\to\hom^2(X;\Z)\]is the usual addition map on cohomology. There’s similarly an “inversion natural transformation” $i:\hom^2(-;\Z)\to\hom^2(-;\Z)$ which, on any space $X$, simply sends a cohomology class to its negation. We can use the natural isomorphism $\hom^2(-;\Z)\simeq[-,\CP^\infty]$ to translate these into natural transformations

\[m:[-,\CP^\infty]\by[-,\CP^\infty]\to[-,\CP^\infty]\,\text{ and }\, i:[-,\CP^\infty]\to[-,\CP^\infty]\]giving a (functorial) group structure to $[X,\CP^\infty]$ for all $X\in\Ho(\push\CW)$ 19 20. By Yoneda, these must arise from some morphisms (i.e. homotopy classes of continuous maps)

\[m:\CP^\infty\by\CP^\infty\to\CP^\infty\,\text{ and }\, i:\CP^\infty\to\CP^\infty\]giving $\CP^\infty$ the structure of a group object in $\Ho(\push\CW)$ (an $H$-space?). Furthermore, we can run this same game with $B(-)$ in place of $\hom^2(-;\Z)$ since $B(X)$, for varying $X$, also has a (functorial) group structure given by taking the tensor product of line bundles. Thus, we arrive at a second pair of maps

\[m':\CP^\infty\by\CP^\infty\to\CP^\infty\,\text{ and }\, i':\CP^\infty\to\CP^\infty\]which also give $\CP^\infty$ the structure of a group object in $\Ho(\push\CW)$. We claim that $(m,i)=(m’,i’)$, so the natural isomorphism $\hom^2(-;\Z)\simeq B(-)$ is an isomorphism of functors $\Ho(\push\CW)\to\Ab$ and not just of functors $\Ho(\push\CW)\to\Set$; put more concretely, our claim gives immediately that $c_1(L\otimes L’)=c_1(L)+c_1(L’)$. In order to prove that $(m,i)=(m’,i’)$, we will show that $\CP^\infty$ has a unique structure as a group object in $\Ho(\push\CW)$.

Recall that $\CP^\infty\simeq K(\Z,2)$ 21, and so a multiplication map $\mu:\CP^\infty\by\CP^\infty\to\CP^\infty$ corresponds to some element of

\[\hom^2(\CP^\infty\by\CP^\infty;\Z)\simeq\hom^2(\CP^\infty;\Z)\oplus\hom^2(\CP^\infty;\Z)\simeq\Z c_1\oplus\Z c_1'.\]Denote this element by $\mu=ac_1+bc_1’$ with $a,b\in\Z$. Let $e:\bracks{* }\to\CP^\infty$ be the identity morphism of its group object structure (i.e. a choice of identity element), so

\[\mu\circ(e\by\Id)=\mu\circ(\Id\by e)=\Id:\CP^\infty\to\CP^\infty.\]In terms of cohomology, these equalities say exactly that $b=a=1$ 22, which is to say we must have $\mu=c_1+c_1’$. Thus, $\CP^\infty$ has a unique structure as a group object in $\Ho(\push\CW)$, so $(m,i)=(m’,i’)$, so $c_1(L\otimes L’)=c_1(L)+c_1(L’)$ ultimately by abstract nonsense + $\CP^\infty$ having simple cohomology.

If you feel like, do the same thing for tensor or symmetric powers of line bundles.

Orientation and Sphere Bundles

Let’s now switch gears. We’ve had some fun defining Chern classes, but didn’t really see how they can be applied to concrete problems. To remedy this defect, we won’t take a look at applications of Chern classes; instead, we’ll define a new characteristic class called the Euler class, and then look at some of its applications.

The Euler class is defined for sphere bundles, but, as we will see later, one can easily make sense of the Euler class of an (oriented) vector bundle as well. For this section, we will be working with real vector bundles instead of complex ones. Do not worry though; we will get back to $\C$ soon enough.

I claimed the Euler class is naturally defined for sphere bundles, so I should at least say what a sphere bundle is.

Before defining Euler classes, let’s tease out the relationship(s) between sphere bundles (the natural homes for Euler classes), real line bundles (the vector bundle analogue of sphere bundles), and complex line bundles (the things I care about).

What about complex vector bundles? Well, given a complex vector bundle $E\to B$ of rank $n$, let $E_\R\to B$ be its underlying real vector bundle (of rank $2n$). This bundle is always orientable (and even oriented). Let $e_1,\dots,e_n$ be a complex basis of $E_b$, so $e_1,ie_i,e_2,ie_2,\dots,e_n,ie_n$ gives a real basis of $(E_\R)_ b$. This defines a canonical orientation of this fiber 23. One can turn this into a cohomology class by considered an (orientation-preserving) map $\Delta^n\to((E_\R)_ b,\punits{E_\R}_ b)$ which represents a homology class $\alpha$, and then considering the unique cohomology class $u_b\in\hom^n((E_\R)_ b,\punits{E_\R}_ b)$ which is a generator and satisfies $\angles{u_b,\alpha}=1$. From naturality of this construction (i.e. it not depending on the complex basis you choose in the beginning), one can show that it gives an orientation of $E_\R\to B$. Hence, for any complex vector bundle $E$, we can obtain an oriented sphere bundle $S(E_\R)$, and so we will be able to make sense of the Euler class of a complex vector bundle.

This concludes our prelims on sphere bundles, so let’s actually define the Euler class now.

Euler Class

We’ll construct the Euler class in a bit of an unusual way. I think one usually first proves a “Thom isomorphism” relating the cohomology of the total space of an oriented real vector bundle $E\to B$ with that of the pair ($E,\units E$) (shifted up $\rank E$ places) via cupping with an “orientation class” $u\in\hom^n(E,\units E;\Z)$. Then, one uses the natural maps $\hom^n(E,\units E;\Z)\to\hom^n(E;\Z)\iso\hom^n(B;\Z)$ to define the Euler class as the image of $u$ in $\hom^n(B;\Z)$. However, I looked up a proof of the existence of this orientation class, and the one I saw seemed long and annoying to the read… so um, we’re gonna do something else and hope no complications arise when we try to prove things about it.

We’ll construct the Euler class via an exercise in my spectral sequence post. Namely, we’ll show that oriented sphere bundles come equipped with a natural long exact sequence in cohomology, and then the Euler class will arise as the image of $1\in\hom^0(B;\Z)$ under a map appearing in this exact sequence.

We can know form the Serre spectral sequence $E_2^{p,q}=\hom^p(B;\hom^q(S^n;\Z))\implies\hom^{p+q}(E)$. We have $E_2^{p,q}=0$ when $q\not\in\{0,n\}$ and so the only page with non-trivial differentials (remember the $E_k$ page has differentials with bidegree $(k,1-k)$) is the $E_{n+1}$ page. Its differentials look like $$\begin{CD} 0 @>>> E_{n+1}^{p,n} @>\d_{n+1}>> E_{n+1}^{p+n+1,0} @>>> 0\\ @. @| @|\\ 0 @>>> \hom^p(B;\Z) @>>> \hom^{p+n+1}(B;\Z) @>>> 0 \end{CD}$$ Thus, the objects of the $E_{n+2}=E_\infty$ page are $$E_\infty^{p,q}=\begin{cases} \hom^p(B;\Z)/\im\d_{n+1} &\text{if }q=0\\ \ker\d_{n+1} &\text{if }q=n\\ 0&\text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$ Thus, the only nonzero objects of the $p$-diagonal of the $E_\infty$-page are $$E_\infty^{p,0}=\hom^p(B;\Z)/\im\d_{n+1}\,\,\text{ and }\,\,E_\infty^{p-n,n}=\ker\d_{n+1}.$$ The elements of the $p$-diagonal of the $E_\infty$-page are successive quotients in a filtration $$0\subset F^p\hom^p(E;\Z)\subset F^{p-1}\hom^p(E;\Z)\subset\cdots\subset F^0\hom^p(E;\Z)=\hom^p(E;\Z),$$ so but most of quotients are $0$. In particular, $E_\infty^{k,p-k}=F^k\hom^p(E)/F^{k+1}\hom^p(E)=0$ for all $k\not\in\{p,p-n\}$, so the above filtration really looks like $$0\subset F^p\hom^p(E;\Z)=\cdots=F^{p-n+1}\hom^p(E;\Z)\subset F^{p-n}\hom^p(E;\Z)=\cdots=\hom^p(E;\Z).$$ Since $F^p\hom^p(E;\Z)\simeq E_\infty^{p,0}$, we have the following exact sequence $$\begin{CD} 0 @>>> F^{p-n+1}\hom^p(E;\Z) @>>> F^{p-n}\hom^p(E;\Z) @>>> E_\infty^{p-n,n} @>>> 0\\ @. @| @| @| \\ 0 @>>> \hom^p(B;\Z)/\im\d_{n+1} @>\alpha'>> \hom^p(E;\Z) @>\beta'>> \ker\d_{n+1} @>>> 0 \end{CD}$$ At this point, we are basically done. Consider the compositions $$\alpha:\hom^p(B;\Z)\to\hom^p(B;\Z)/\im d_{n+1}\xto{\alpha'}\hom^p(E;\Z)$$ and $$\beta:\hom^p(E;\Z)\xto{\beta'}\ker d_{n+1}\into\hom^{p-n}(B;\Z).$$ These fit into a sequence $$\cdots\too\hom^{p-n-1}(B;\Z)\xtoo{d_{n+1}}\hom^p(B;\Z)\xtoo{\alpha}\hom^p(E;\Z)\xtoo{\beta}\hom^{p-n}(B;\Z)\xtoo{d_{n+1}}\hom^{p+1}(B;\Z)\too\cdots$$ which we claim is exact. First, $\alpha'$ is injective, so we have $\ker\alpha=\im\d_{n+1}$ which gives exactness at $\hom^p(B;\Z)$. Second, $\ker\beta=\ker\beta'=\im\alpha'=\im\alpha$ so we get exactness as $\hom^p(E;\Z)$ as well. Finally, $\beta'$ is surjective so $\im\beta=\ker\d_{n+1}$ which gives exactness at $\hom^{p-n}(B;\Z)$. Thus the above long sequence is exact everywhere, and we win.

Also show that $\alpha:\hom^p(B;\Z)\to\hom^p(E;\Z)$ is just the pullback $\pull\pi$ along the projection $\pi:E\to B$.

When $p=n$, the sequence includes the map $\beta:\hom^n(E;\Z)\to\hom^0(B;\Z)$. Show that composing this with the natural map $\hom^0(B;\Z)\iso\hom^n(S^n;\Z)$ gives the usual restriction map $\hom^n(E;\Z)\to\hom^n(S^n;\Z)$.

The only property of the Euler class that I think we will need to know for now is that it is functorial. The point here is that the Serre spectral sequence is itself functorial (this is clear from its construction), and so given a pullback

\[\begin{CD} S^n @>>> \pull fE @>>> B'\\ @| @VVgV @VVfV \\ S^n @>>> E @>>> B \end{CD}\]of sphere bundles, one obtains a commutative square.

\[\begin{CD} \hom^0(B';\Z) @>\d>> \hom^{n+1}(B';\Z)\\ @A\pull fAA @AA\pull fA \\ \hom^0(B;\Z) @>>\d> \hom^{n+1}(B;\Z) \end{CD}\]The left vertical map sends $1\mapsto1$, and so by commutativity, we see that

\[\pull fe(E)=\pull f\d(1)=\d\pull f(1)=\d(1)=e(\pull fE),\]which says exactly that the Euler class is functorial. 24

Now that we have seen a direct construction of the Euler class, let’s return to this whole “Thom isomorphism” thing I alluded to earlier. The main point of this thing was/is to construct a Thom/orientation class $u\in\hom^n(E,\units E;\Z)$ for an oriented vector bundle $E\to B$. I prefer to think in terms of sphere bundles, so we are really after a certain cohomology class $u\in\hom^n(D(E), S(E);\Z)$ where, given a rank $n$ oriented vector bundle $E\to B$, $S(E)$ as usual denotes its associated unit sphere bundle and $D(E)$ denotes its analogously defined unit disk bundle $D(E)\to B$ (with fibers homeomorphic to the $n$-disk, $D^n$). Let’s take things one step further. Say, as has been the case in this section, we start with an oriented $S^n$ bundle $E\to B$ instead. How should we obtain a Thom class now? The first thing we would like to do is “fill in” the fibers of this bundle in order to obtain a $D^{n+1}$-bundle $D(E)\to B$ with $E$ as its “fiberwise boundary.” Then, the Thom class will be a certain cohomology class $u\in\hom^{n+1}(D(E),E;\Z)$ 25.

With that said, let $D(E):=M_\pi$ be the mapping cylinder $$M_\pi:=(E\by I)\cup_{(E\by\{0\})}B=\parens{(E\by I)\sqcup B}/((e,0)\sim\pi(e)),$$ and let $p:D(E)\to B$ be the natural "projection to the base" map (i.e. $p(e,t)=\pi(e)$ for $(e,t)\in E\by I$ and $p(b)=b$ when $b\in B$). Then, by construction, for any $b\in B$, we have $$\inv p(b)=M_{\pi\vert_{\inv\pi(b)}}=(\inv\pi(b)\by I)\cup_{(\inv\pi(b)\by\bracks0)}\bracks b=(\inv\pi(b)\by I)/(\inv\pi(b)\by\bracks0)=C\inv\pi(b)\cong D^{n+1}.$$ Furthermore, by restricting the locally trivial neighborhoods for $\pi$, we see that $p$ is still a fiber bundle. Finally, the map $E\into D(E)$ is simply $e\mapsto(e,1)$.

At this point, we will take some things on faith to avoid repeating ourselves 26. Let $\pi:E\to B$ be an oriented $S^n$-bundle as usual. By the proposition above, we have a “fiber sequence pair” $(D^{n+1}, S^n)\to(D(E), E)\to B$. Given this, just as we used the Serre spectral sequence for the fibration $S^n\to E\to B$ in order to construct the Euler class, one can use the Serre spectral for the fiber sequence pair $(D^{n+1}, S^n)\to(D(E), E)\to B$ (i.e. a spectral sequence $E_2^{p,q}=\hom^p(B;\hom^q(D^{n+1},S^n;\Z))\implies\hom^{p+q}(D(E),E;\Z)$) to construct a Thom class $u=u(E)\in\hom^{n+1}(D(E),E;\Z)$ 27. This Thom class is constructed so that the map 28

\[\mapdesc{\phi}{\hom^p(B;\Z)}{\hom^{p+n+1}(D(E),E;\Z)}{\alpha}{\pull\pi(\alpha)\smile u}\]is an isomorphism for all $p$. Furthermore, this map gives the below isomorphism of exact sequences between the Gysin sequence and the long exact sequence for the pair $(D(E),E)$. Recall that $(D^{n+1},S^n)\to(D(E),E)\xto{(p,\pi)}B$ is our pair of fiber bundles over $B$, and that the fibration $p:D(E)\to B$ is a homotopy equivalence since the fiber is contractible.

\[\begin{CD} \cdots @>>> \hom^p(B;\Z) @>\pull\pi>> \hom^p(E;\Z) @>>> \hom^{p-n}(B;\Z) @>\smile e(E)>> \hom^{p+1}(B;\Z) @>>> \cdots\\ @. @V\pull pVV @V\Id VV @VV\phi V @VV\pull pV\\ \cdots @>>> \hom^p(D(E);\Z) @>>> \hom^p(E;\Z) @>>> \hom^{p+1}(D(E),E;\Z) @>>> \hom^{p+1}(D(E);\Z) @>>> \cdots \end{CD}\]In particular, the Euler class $e(E)\in\hom^{n+1}(B;\Z)$ is the preimage of the restriction $u(E)\vert_{D(E)}\in\hom^{n+1}(D(E);\Z)$ of the Thom class to the total space.

Relation to Chern Classes

We haven’t thought about classifying spaces in a while; let’s change that. Let $E\to B$ be a rank $n$ complex vector bundle. This gives rise to an oriented $S^{2n-1}$-bundle $S(E_\R)\to B$, and so we can define the Euler class of the complex vector bundle $E\to B$ as

\[e(E):=e(S(E_\R))\in\hom^{2n}(B;\Z).\]We saw at the end of the last section that the Euler class is functorial as a cohomology class of sphere bundles, and this extends to its functoriality as a cohomology class of complex vector bundles. Thus, just as with all characteristic classes of complex vector bundles, the Euler class (on complex vector bundles) must really correspond to some universal cohomology class

\[e\in\hom^{2n}(BU(n);\Z)\simeq\Z[c_1,c_2,\dots,c_n]_ {2n}\,\,\,\,\text{ where }c_i\in\hom^{2i}(BU(n);\Z).\]We aim to figure out which class it is. Necessarily, $e=p(c_1,c_2,\dots,c_n)$ is some polynomial in the Chern classes, and so we just need to determine which one it is. Determining a polynomial in Chern classes is exactly the type of situation one uses the splitting principle for, and so we are instantly reduced to determining the Euler class of a sum $L_1\oplus\dots\oplus L_n$ of line bundles. This will have two parts; what’s the Euler class of a line bundle, and what’s the Euler class of a sum of 2 line bundles? Once we know these, we just induct and have our answer in general.

We will start with computing the Euler class of a sum of line bundles, so let $L_1\xto{\pi_1}B$ and $L_2\xto{\pi_2}B$ be complex line bundles. Note that their “internal direct sum” $L_1\oplus L_2\to B$ is the pullback of their “external direct sum” $L_1\by L_2\to B\by B$ along the diagonal map $\Delta:B\to B\by B,b\mapsto(b,b)$. That is, we have a pullback diagram.

\[\begin{CD} L_1\oplus L_2 @>>> L_1\by L_2\\ @V\pi_1\oplus\pi_2VV @VV\pi_1\by\pi_2V\\ B @>>\Delta> B\by B \end{CD}\]Now, we can compute $e(L_1\oplus L_2)$ using functoriality + knowledge of the cohomology of a product. We have $\ast\hom(B\by B;\Z)\simeq\ast\hom(B;\Z)\otimes\ast\hom(B;\Z)$ and, by considering the two projections $B\by B\rightrightarrows B$, one sees that $e(L_1\by L_2)=e(L_1)\otimes e(L_2)\in\hom^4(B\by B;\Z)$. Pulling back along the diagonal maps corresponds to taking cup products, so

\[e(L_1\oplus L_2)=\pull\Delta e(L_1\by L_2)=e(L_1)\smile e(L_2)\in\hom^4(B;\Z).\]Thus, in general, the Euler class $e(L_1\oplus L_2\oplus\cdots\oplus L_n)$ of a sum is the product $e(L_1)e(L_2)\dots e(L_n)$ of the Euler classes.

We still need to determine the Euler class of a line bundle in terms of its first Chern class. That is, it is clear that $e(L)=kc_1(L)$ for some $k\in\Z$ independent of $L$, but we still don’t know $k$ 29. Luckily, we can determine $k$ by looking at a simple universal case. Recall that $BU(1)\simeq\CP^\infty$, and let $\iota:\CP^1\into\CP^\infty\simeq BU(1)$ be the natural inclusion map, so $\pull\iota:\hom^2(BU(1);\Z)\iso\hom^2(\CP^1;\Z)$ is an isomorphism. Thus, we are reduced to determining the Euler class of the tautological line bundle $E\to\CP^1$ on $\CP^1$. This is the line bundle whose fiber above a point $\l\in\CP^1$ is the line $\l\subset\C^2$ represented by that point. Hence, by definition, we see that the sphere bundle $S(E_\R)$ associated to it is the Hopf fibration

\[S^1\to S^3\to S^2.\]The Euler class of this bundle comes from the differential on the $E_2$-page of its Serre spectral sequence. That page looks like

\[\begin{array}{c | c c c c} \tbf q & \\ 1 & \hom^0(S^2;\hom^1(S^1))\simeq\Z a & 0 & \hom^2(S^2;\hom^1(S^1))\simeq\Z c_1a\\ 0 & \hom^0(S^2;\hom^0(S^1))\simeq\Z & 0 & \hom^2(S^2;\hom^0(S^1))\simeq\Z c_1 \\\hline & 0 & 1 & 2 & \tbf p \end{array}\]where $a\in\hom^2(S^1)$ is the preferred generator and $c_1\in\hom^2(S^2)$ is the first Chern class of the tautological line bundle $E\to\CP^1\simeq S^2$. The only nontrivial differential on this page (or any page thereafter) is $\d_2:\Z a\to\Z c_1$. Since neither $\Z a$ nor $\Z c_1$ survive to the $E_\infty$-page (the $1$- and $2$-diagonals of the $E_\infty$-page are all $0$ since $\hom^2(S^3)=\hom^1(S^3)=0$), we see that this map must be an isomorphism, so $d_2(a)=\pm c_1$. Since, by definition, $e(E)=d_2(a)$, we see that $e(E)=\pm c_1(E)$.

Thus, for a general complex line bundle $L\to B$, we have $e(L)=\pm c_1(L)$. In particular, if $L$ is given the “correct” orientation, then $e(L)=c_1(L)$. Since $L$, being a complex line bundle, comes equipped with a canonical orientation, one suspects that this one (its complex orientation) is the correct one, and so that we can safely write $e(L)=c_1(L)$ (implicitly endowing $L$ with its complex orientation). This is indeed the case, but I’m not sure if we will be able to show it 30.

In any case, we can cheat. Let’s just adopt the convention that when we write $e(L)$ for $L$ a complex line bundle, we’re implicitly taking its Euler class with respect to the “correct” orientation (i.e. always $L$’s complex orientation or never $L$’s complex orientation), and, having adopted this convention, we can now safely write $e(L)=c_1(L)$. Combining this with the fact that $e(L_1\oplus L_2)=e(L_1)e(L_2)$ and with the splitting principal, one sees that for a general complex vector bundle $E\to B$, we have 31

\[e(E)=c_n(E).\]Relation to Obstruction Theory

This sign issue we ran into will be resolved in the next section. In the current one, we’ll look at what might be our first actual application of characteristic classes in this post: the Euler class gives an obstruction to the existence of (non-vanishing) sections. In other words, if your Euler class is nonzero, then your sphere bundle has no sections.

One can naturally wonder if the converse is true. That is, if $e(E)=0$, then must there necessarily be a section of $\pi$? The answer to this turns out to be no, and the issue is essentially that $S^n$ has higher homotopy groups 32 beyond the $\pi_n(S^n)\simeq\Z$ from which the Euler class ultimately originates. In general, when faced with lifting problems like this (can you lift a map against a fibration, possibly extending an initial lift on some subspace), one obtains a sequence $\omega_k\in\hom^{k+1}(\text{blah};\pi_k(F))$ ($F$ the fiber) of cohomology classes such that a lift exists iff all of these cohomology classes vanish. In this framework, the Euler class $e(E)\in\hom^{n+1}(B;\Z)=\hom^{n+1}(B;\pi_n(S^n))$ is what’s called a primary obstruction class since it is the first one which can be nonzero in the situation of constructing a section of a sphere bundle 33.

Relation to Enumerative Geometry

This is the most exciting part of this whole post. The Euler class. can. be. used. to. count.

We will make sense of this in this section, and then end the post with an example. By using the Euler class to count, I mean that the Euler class, in nice situations, encodes the number of zeros of a generic section of its vector bundle. Essentially, we will refine the result that a bundle with a section with $0$ zeros has Euler class equal to $0$.

For this application, we will need not just the Euler class itself, but also the Thom class. Before, proving things, let’s recall Poincare duality.

As suggested by the fact that we recalled the above theorem, for the results of this section, we will need to assume our base space in a compact manifold. Given this, we will show that the Euler class of an oriented real vector bundle is Poincare dual to the zero set of a generic section of the bundle. When the dimension of the base space equals the rank of the bundle, the a generic section will have a zero-dimensional zero set (i.e. a finite, discrete set of zeros), and so in that case, the Euler class will simply count the number of zeros.

The above lemma is our first inclination that the Thom class (and hence the Euler class) has anything to do with sections of its bundle. Next, we will show how one can use Thom classes to construct the cohomology class dual to a submanifold $N\subset M$. For notational convenience, given a compact, oriented $k$-dimensional submanifold $\iota:N\into M$ (here, $\dim M=n$), let $\ast{[N]}\in\hom^{n-k}(M;\Z)$ denote the Poincare dual to $\push\iota[N]\in\hom_k(M;\Z)$.

Now, let’s take a very brief detour into the theory of vector bundles on smooth manifolds. Let $N\into M$ be compact, oriented smooth manifolds of dimensions $k$ and $n$, respectively. Then, there exists vector bundles $TN\to N$ and $TM\to M$ of ranks $k$ and $n$, respectively, called the tangent bundles of $N$ and $M$. In particular, $TN$ is a subbundle of $TM\vert_N$, the tangent bundle of $M$ restricted to $N$, and so fits into an exact sequence (of vector bundles on $N$)

\[0\too TN\too TM\vert_N\too N_{N/M}\too0,\]where the rank $(n-k)$ vector bundle $N_{N/M}$ is by definition the normal bundle of $N$ in $M$. Intuitively, the tangent bundle $TM$ contains all the directions one can move along in $M$ (and similarly for $TN$), so the normal bundle $N_{N/M}$ contains all the directions in $M$ which are perpendicular to $N$. The amazing fact is that there exists a “tubular neighborhood” $U\subset M$ of $N$ with a smooth embedding $U\into N_{N/M}$ sending $N\subset U\subset M$ to the zero section in $N_{N/M}$; in other words, the (unit disk bundle of) the normal bundle embeds back into the manifold. Accepting this, attached to $N\into M$ is a Thom class

\[u_N:=u(N_{N/M})\in\hom^{n-k}(D(N_{N/M},S(N_{N/M});\Z)\simeq\hom^{n-k}(U,U\sm N;\Z).\]By excision, we have an isomorphism $\hom^{n-k}(M,M\sm N;\Z)\to\hom^{n-k}(U,U\sm N;\Z)$, and this former space naturally restricts to $\hom^{n-k}(M;\Z)$. Let $u_N^M$ denote the image of $u(N_{N/M})$ under the composite map

\[\hom^{n-k}(D(N_{N/M}),S(N_{N/M});\Z)\iso\hom^{n-k}(U,U\sm N;\Z)\iso\hom^{n-k}(M,M\sm N;\Z)\to\hom^{n-k}(M;\Z).\]This $u_N^M$ is the Poincare dual of $N$.

If one is more careful above (actually, more careful in the first lemma of this section), then they can remove the $\pm$, and just conclude that $\ast{[N]}=\pm u_N^M\in\hom^{n-k}(M;\Z).$ However, what we have above is good enough for our purposes; in the end, we’ll want to count zeros of a section, and so we’ll know that the correct answer will be a positive number. We’ll obtain a result saying that the Euler class computes this count up to sign, so we can always get the correct result by computing the Euler class and then taking the absolute value of what we get.

At this point one may reasonably wonder why this is such a big deal. The point (at least my point) is the following: say you want to calculate the number of some type of geometric object. It often happens that the objects you want to count are given by zero set of a well-chosen section on a suitable line bundle. Once you realize this in your specific case, the above theorem tells you that computing this count amounts to calculating a characteristic class. Even if calculating characteristic classes isn’t your thing, the theorem still tells you that your geometric count is (largely) independent of the section you choose to count it! That means, even if you problem naturally presents you with one section of your line bundle, the above results says you can resolve it by counting the zeros of the section which is easiest to work with!

Let’s see some of this in action.

27 Lines on a Cubic

As is probably unsurprising by this point, we will end this post by determining the number of lines (copies of $\CP^1$) on a (complex) cubic surface. Let $F=F(x,y,z,w)$ be a degree 3 homogeneous polynomial, and let $X=\bracks{F=0}\subset\CP^3$ be the cubic surface it determines. What can one count the number of lines on $X$?

Well, consider $G=\mrm{Gr}(2,4)$ (or $\mrm{Gr}(1,3)$ depending on who you ask), the Grassmannian manifold consisting of $2$-dimensional subspaces of $\C^4$ (equivalently, of lines in $\CP^3$). Note that, as a complex manifold, the dimension of $G$ is $2(4-2)=4$. On $G$, one has the tautological subbundle

\[S=\bracks{(v,p):v\in p}\subset\C^4\by G\to G\]which is a rank $2$ holomorphic vector bundle $S\to G$ whose fiber $S_p$ above a point $p\in G$ is the plane represented by that point. Consider the dual bundle $\dual S=\Hom(S,\C)\to G$ whose fiber $\dual S_p$ over a point $p\in G$ is the space of linear functions $S_p\to\C$. Since $S_p\subset\C^4$, we see that every linear functional $S_p\to\C$ is the restriction of some linear functional $\C^4\to\C$ on $\C^4$ (i.e. $\dual{(\C^4)}\to\dual S_p$ is surjective for all $p$). Letting $x,y,z,w$ suggestively denote a fixed basis for $\C^4$, we get that every linear functional on $\C^4$ (and so every linear functional on $S_p$) is given by some homogeneous linear polynomial in $x,y,z$, and $w$. That is, sections of $\dual S\to G$ correspond to homogeneous linear polynomials in the variables $x,y,z,w$. Thus, forming the symmetric bundle $\Sym^3\dual S\to G$, we get that sections of it correspond to homogeneous degree $3$ polynomials in $x,y,z,w$. In particular, there exists a section $\sigma_F:G\to\Sym^3\dual S$ corresponding to the polynomial $F$ used to define our cubic surface $X$!

Now, what does it mean for some $p\in G$ to be a zero of $\sigma_F$, i.e. when is $\sigma_F(p)=0$? Well, $\sigma_F(p)\in\Sym^3\dual S_p$ is the linear functional $F\in\Sym^3\dual{(\C^4)}$ restricted to the plane $S_p\subset\C^4$, so $\sigma_F(p)=0$ if and only if $F(c_1,c_2,c_3,c_4)=0$ for all $c_1x+c_2y+x_3z+c_4w\in S_p\subset\C^4$ (here, $c_i\in\C$). That is, $\sigma_F(p)=0$ iff $F$ vanishes along the plane $S_p\subset\C^4$. Now, we observe that a $2$-plane in $\C^4$ in precisely a line in $\CP^3$, so points of $G$ can be viewed a parameterizing all the lines on $\CP^3$, given some $p\in G$, we have $\sigma_F(p)=0$ if and only if $F$ vanishes along the line (in $\CP^3$) represented by $p$. In other words, $\sigma_F(p)=0$ iff the line $p\subset\CP^3$ lives in the set $\bracks{F=0}=:X$; the zeros of $\sigma_F$ are precisely the lines in $X$!

This brings us to the home stretch. Since $\rank S=2$, we easily see that $\rank\Sym^3\dual S=4=\dim_\C G$, so the number of lines on $X$ is (Poincare dual to) $c_4(\Sym^3\dual S)$. Let’s compute this. By the splitting principle, to determine $c_4(\Sym^3\dual E)$ for a general (rank 2) vector bundle $E$, we can assume that $E=L_1\oplus L_2$ is a sum of line bundles. Let $x_1=c_1(L_1)$ and $x_2=c_1(L_2)$, so $c(E)=(1+x_1)(1+x_2)=1+(x_1+x_2)+x_1x_2$. Note that

\[\Sym^3\dual E=\Sym^3(\dual L_1\oplus\dual L_2)=(\dual L_1)^{\otimes 3}\oplus((\dual L_1)^{\otimes2}\otimes\dual L_2)\oplus(\dual L_1\otimes(\dual L_2)^{\otimes2})\oplus(\dual L_2)^{\otimes3}.\]Thus, taking the total Chern class of both sides, we see that

\[\begin{align*} c(\Sym^3\dual E) &=(1-3x_1)(1-2x_1-x_2)(1-x_1-2x_2)(1-3x_2)\\ &=1 - 6(x_1+x_2) + (11x_1^2+32x_1x_2+11x_2^2) - 6(x_1^3 + 8x_1^2x_2 + 8x_1x_2^2 + x_2^3) + x_1x_2(18x^2 + 45x_1x_2 + 18x_2^2)\\ &= 1 - 6c_1(E) + (11c_1(E)^2 + 10c_2(E)) - 6(c_1(E)^3 + 5c_1(E)c_2(E)) + c_2(E)(18c_1(E)^2 + 9c_2(E)) \end{align*}\]Thus, for any rank $2$ complex vector bundle $E\to B$, we have

\[c_4(\Sym^3\dual E)=c_2(E)(18c_1(E)^2 + 9c_2(E)).\]Um, now we switch gears and cheat. I actually don’t know a quick and easy way to calculate the above cup products 34, so we won’t compute them. Instead, we’ll use the observation that $c_4(\Sym^3\dual S)$ can be computed using the zeros of any of its sections in order to determine the number of lines on $X$.

That is, at this point, we know that the number of lines on $X$ is given by $c_4(\Sym^3\dual S)$ for $S\to\mrm{Gr}(2,4)$ the tautological subbundle. This has absolutely no dependence on $X$, so we know already that every cubic surface (over $\C$) has the same number of lines! Thus, it suffices to just pick one and count how many lines it has. For this, we introduce the Fermat cubic surface

\[X:x^3+y^3+z^3+w^3=0.\]Up to a permutation of coordinates, every line in $\CP^3$ is given by two linear equations of the form $x=az+bw$ and $y=cz+dw$ for some $a,b,c,d\in\C$. This will lie on $X$ if and only if

\[(az+bw)^3+(cz+dw)^3+z^3+w^3=0\]as polynomials in $\C[z,w]$. Equating coefficients, this means that we need

\[\begin{align*} a^3 + c^3 &= -1\\ b^3 + d^3 &= -1\\ a^2b &= -c^2d\\ ab^2 &= -cd^2 \end{align*}\]If $a,b,c,d$ are all non-zero, then

\[a^3=(a^2b)^2/(ab^2)=-(c^2d)^2/(cd^2)=-c^3\implies0=a^3+c^3=-1,\]which is nonsense. Hence, possibly after renaming, we may assume $a=0$. Then, $c^3=-1$, so $d=0$ and $b^3=-1$ as well. This gives $9$ (since $3$ cube roots of $-1$) possible choices of $(a,b,c,d)$ giving rise to $9$ distinct lines on $X$. These lines are

\[x=\zeta_3^iw\,\,\,\,\text{ and }\,\,\,\,y=\zeta_3^jz\]for some $i,j\in\bracks{0,1,2}$. The rest of the lines are given by permuting the coordinates. Base on the form these lines take, we see that we get a set of $9$ lines for every partition of the set $\bracks{x,y,z,w}$ into subsets of size $2$. Thus, there are $9\cdot3=27$ lines on $X$, and so $27$ lines on any complex cubic surface.

-

This may make more sense by the end of the post if it doesn’t right now, but because of the existence of classifying spaces, characteristic classes can equivalently be thought of as cohomology classes in $\ast\hom(BU(n);A)$ for some $n$ (the rank of the vector bundle) and abelian group $A$, assuming you only care about complex vector bundles. ↩

-

No promises ↩

-

I didn’t quite meet this goal. Started strong but ran into issues by the end (lacking details once I start talking about Euler classes) as seems to be the norm. ↩

-

Except in footnotes where I’ll reserve the power to be vague, to be handwavy, to give potentially bad intuition, and to say potentially incorrect things. ↩

-

I will admit that thinking in terms of e.g. integrating differential forms is more intuitive than in terms of e.g. cupping cohomology classes. However, tough luck; I like working abstractly even when intuiting actually geometry ↩

-

Some things I say may be false without this. For example, I think you need this for fiber bundles to be fibrations. ↩

-

“Isn’t $-\gamma$ also a generator?” you ask. Yes, but it’s actually a different one. The point is that $\CP^2$ has a complex structure, so a canonical orientation, so a canonical choice of generator $\gamma\in\hom^2(\CP^2;\Z)$, and this is “the same” generator we use for $\hom^2(\CP^\infty;\Z)$. ↩

-

Ostensibly, $BU(n)$ characterizes principal $U(n)$-bundles, not complex rank-$n$ vector bundles, so what gives? Well, two things: (1) every complex rank $n$ vector bundle arises from some principal $U(n)$-bundle and (2) the universal rank $n$ vector bundle is the vector bundle $(EU(n)\by_{U(n)}\C^n)\to BU(n)$ over $BU(n)$ where $U(n)$ acts on $\C^n$ by matrix-vector multiplication as one would expect ↩

-

Fix any $x\in U_i\cap U_j$. The point $(x,v)\in\inv p(U_i)\simeq U_i\by\C^{n+1}$ is identified with the point $(x,\tau_{ij}(x)v)\in\inv p(U_j)\simeq U_j\by\C^{n+1}$. ↩

-

$\pull\pi E\vert_{\P(E)_ b}\simeq\C^{n+1}\by\P(E)_ b$ is trivial since it is pullback from a vector bundle over a point. That is, letting $q=\pi\vert_{\P(E)_ b}:\P(E)_ b\to{b}$, we have $\pull\pi E\vert_{E_b}\simeq\pull qE_b\simeq\C^{n+1}\by\P(E)_ b$. ↩

-

It is $\ints{\P^n}(-1)$ if you are familiar with this notation. ↩

-

I really should have started with a rank $n$ vector bundle. ↩

-

As the notation suggests, these coefficients are exactly the Chern classes of $E$. I think I’ve heard that this way of obtaining Chern classes was discovered by Grothendieck, but don’t quote me on that. ↩

-

Above, one should really write $\pull\pi c_1(EU(n))$ for $\pi:BU(n-1)\by BU(1)\to BU(n)$ instead of just $c_1(EU(n))$. ↩

-

$c_1$ corresponds to the first Chern class on the first factor, and $c_1’$ corresponds to the first Chern class on the second factor. ↩

-

I think that’s how people usually prove algebraic independence of symmetric polynomials ↩

-

This is not the simplest way to do this, but more practice with Yoneda-type reasoning is never bad ↩

-

Strictly speaking, $X$ does not need to have the homotopy type of a CW-complex, but if it doesn’t you need to be extra careful. In particular, $\hom^2(X;\Z)$ would not represent singular cohomology, but instead singular cohomology of a CW approximation. ↩

-

We use the same letters to denote these technically different maps in order to emphasize how closely related they are, and totally not because I was too lazy to come up with new names. ↩

-

Also, I should have also include an “identity natural transformation” $e:\bracks{0}\to\hom^2(-;\Z)$, but oh well. ↩

-

$\CP^\infty$ is like unironically the best topological space; fight me ↩

-

e.g. the cohomology class corresponding to $\mu\circ(e\by\Id)$ is $ac_1\in\Z c_1’=\hom^2(\CP^\infty;\Z)$ (cohomology of right factor of $\CP^\infty\by\CP^\infty$). One sees by tracing identifications that forming the cohomology class corresponding to $\mu\circ(e\by\Id)$ amounts to pulling back $\mu$’s cohomology class along the map $e\by\Id:\CP^\infty\to\CP^\infty\by\CP^\infty$. ↩

-

There are many equivalent definitions of orientations of various objects. One way to define the orientation of a real vector space $V$ is by saying that it is a connected component of $\Wedge^{\dim V}V\sm{0}$. In other words, it is an equivalence class of ordered bases where two bases are considered equivalent if they differ by a matrix with positive determinant. ↩

-

In case you’re wondering where we used that we were considering the pullback bundle $\pull fE\to B’$ of $E$ and not just an arbitrary vector bundle $E’\to B’$ over $B’$ with a map $E’\to E$ to $E$ (lying over the given map $B’\xto fB$), the answer is no where. In general, if $E’\to E$ is a bundle map over $B’\xto fB$, then $E’\simeq\pull fE$. ↩

-

I think one of my worse decisions this post has been to use the same symbol $E$ as the default for all my fiber bundles, whether they be (oriented) real (or complex) vector bundles, sphere bundles, principal $G$-bundles, or what have you ↩

-

In case you are wondering, yes, I could just restructure this post by showing the existence of the Thom class first and then using its existence to define the Euler class in order to avoid this omission ↩

-

Going through this yourself might be good practice. You should end up getting that $\hom^{p+n+1}(D(E),E;\Z)\simeq\hom^p(B;\Z)$ and that the Thom class $u\in\hom^{n+1}(D(E),D;\Z)$ is the unique cohomology class restricting to the preferred generator of $\hom^{n+1}(D^{n+1},S^n;\Z)\simeq\hom^n(S^n;\Z)$ on each fiber. ↩

-

You may want a relative version on Leray-Hirsch to prove this ↩

-

At this point, I don’t even think we know that $k\neq 0$. ↩

-

Computing differentials in spectral sequences is hard… I spent ~3 hours trying to carefully work this out because I couldn’t find a source that does it (all the ones I saw either defined $c_1(L)=e(L)$ or showed $c_1(L)=\pm e(L)$ and left it at that), and in the end, I concluded that if I didn’t stop thinking about it, I’d lose my mind. ↩

-

I don’t think I remarked this earlier, but from the multiplicativity $c(E\oplus F)=c(E)c(F)$ of the total Chern class, one sees that $c_{\mrm{top}}(E\oplus F)=c_{\mrm{top}}(E)c_{\mrm{top}}(F)$. In particular, $c_n(L_1\oplus\cdots\oplus L_n)=c_1(L_1)\dots c_1(L_n)$ when $L_1,\dots,L_n$ are line bundles ↩

-

If $B$ does not have higher cohomology groups (i.e. if $\hom^k(B)=0$ for all $k>n+1$), then it is true that existence of a section is equivalent to vanishing of the Euler class ↩

-

Technically speaking, the primary obstruction class has its own definition and we haven’t shown that it equals the Euler class yet, but it does. ↩

-

Note that the coefficients, $18$ and $9$, add up to $27$. Also note that, even without being able to determine these cup products, we can conclude that the number of lines on a cubic surface must be some multiple of $9$ (independent of the chosen surface). ↩