Imagine you and another person commit a crime together. Futhermore, imagine it was the perfect crime – completely foolproof – except it wasn’t – because the cops are pretty sure you two did it. In fact, they know it was you two; the only thing stopping them from locking both of you up in jail for a very, very long time right now is this stupid burden of proof reminding them their evidence isn’t completely airtight 1. They could do some footwork and get more proof, but a confession seems easier. They have enough evidence to temporarily arrest you and your crime mate, and question you in jail for a couple nights.

The first night, you two are separated. One cop takes you to an interrogation room, and offers you a deal. “Look. I know you did this. You know you did this. Everyone here knows you did this. We’re gonna keep you in here for a couple days, then we’re gonna get the rest of the evidence we need and you’ll spend the rest of you life behind bars. Or, we can work together. Getting evidence is annoying. I already know you and your partner did this, so I’d rather just put one of you away now. Confess. Rat on your partner, and we’ll give you a reduced sentence.” At the same time, another cop took your crime mate to a different room, and gave him the same speech. You both have the choice giving up your partner in crime to help yourself, or staying quiet. Let’s say if you both rat each other out, you both get 2 life sentences in jail; if you both keep quiet, there’s only enough evidence found for you both to get 1 life sentence; and if you rat him out, but he doesn’t rat you out, you get no jail time and he gets 3 life sentences 2. What would you do? Would you turn on your partner, or keep quiet? This is an example of what’s called a Prisoner’s Dilema.

Aside

The scenario above might seem a little contrived, and like it’s not something work considering, but Prisoner’s Dilemas show up in other places too. The main thing that makes a situation a Prisoner’s Dilema is that you can screw someone over, or help them at your expense. Another example of this is working on a partnered project 3. You can put in a lot of work (at the expense of having to go through the trouble of putting in work), or be lazy and let your partner do everything themselves. Another example is performance-enhancing drugs in sports. There are two competing athletes. Each athlete can take drugs (making them better than an undrugged opponent, but giving them health and legal risks) or compete all natural.

What do you do?

Let’s return to our original example of a Prisoner’s Dilema, and see if we can figure out what we should do. There are two people, you an your partner. You can each (D)efect from your partner by turning on him, or (C)ooperate with him by staying quiet. Depending on what the two of you choose, you’ll be in jail for some number \(y\) of life sentences, and you want to minimize this number. Personally, I’ve often heard that people should strive for greatness, so I think we should tweak this so you want to maximize something instead4. That being said, minimizing \(y\) is the same as maximizing \(3-y\), so we’ll do that. All of this can be nicely represented using the matrix5 below

\[\begin{array}{l | c | r |} & C & D\\ \hline C & 2,2 & 0,3 \\ \hline D & 3,0 & 1,1 \\ \hline \end{array}\]The above says, for example, that if the first (row) player6 defects while the second (column) player player cooperates, then the first player gets 0 life sentences (3-0=0) and the second gets 3 life sentences (3-3=0). As another example, it says if both player cooperate, then they both get 1 (3-1=2) life sentence.

If you look at this matrix for a while, it might become clear what you should do. No matter what your partner does, it is always better for you to defect than to cooperate7, so you should rat out your partner8. However, this matrix is symmetric, and so by the same reasoning, your partner should rat you out too. Thus, it makes sense to predict that in this situation, you’ll both defect and spend 2 life sentences in jail.

Wait, what?

Hopefully, the argument above makes sense. It’s always in your best interest to defect, and so you should always defect. You and your partner will both want to do what’s in your individual best interests, so you’ll both defect. Logically, this makes perfect sense, but it feels wrong. You could both cooperate instead and both spend less time in jail. This is where the dilema lies: defecting is clearly better, but it would be nice if you both cooperated. The issue with you both cooperating though is that you don’t communicate with each other beforehand, and so if you cooperate, you don’t know that your partner will as well. But let’s say that’s not the case. Let’s say you and your partner expected the cops to do something like this once you knew they were on to you, and so you agreed beforehand to both cooperate. That’s it. Problem solved, right? Wrong. If you both swore to cooperate, and you believed wholehartedly that your partner was going to cooperate, then it would be in your best interest to defect! Why go to jail for 1 life sentence, when you could go for none instead? It doesn’t stop there, though. Your partner can use this same logic to decide that he should go back on his word and defect instead too, so even if you agree ahead of time to cooperate, it still seems reasonable to expect that you will both defect.

So maybe there’s no escaping the both of you defecting. Maybe that’s just what’s meant to happen. Maybe, but maybe not. Despite all these valid arguments against it, it can still feel like you and your partner should just both cooperate. As we have modelled things now, there isn’t really a way of interpreting this so that we can safely arrive at this conclusion, so maybe we’re modelling this situation incorrectly.

There’s only 1 interrogation room

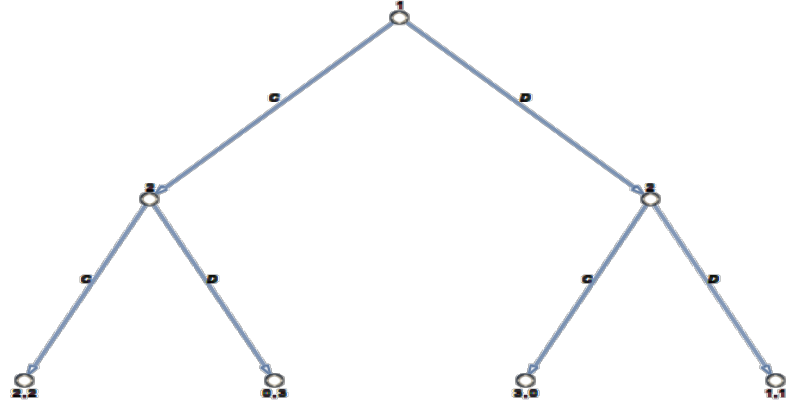

In our current model, you and your partner essentially move simultaneously. The cops separate you, offer both of you deals, and then you respond before knowing what the other did. This might not be completely realistic. Maybe the cops took you away before taking your partner away and so you were able to somehow communicate with him what you did. Maybe there’s only 1 interrogation room, so you had to go one at a time and the other was able to figure out what the first one did. Maybe you didn’t commit a crime and there’s no police involved and you’re actually in a different prisoner’s dilema where it makes more sense to think about you two moving one at a time (like drugs in sports)9. It doen’t matter the reason. Let’s just say you decide to defect or cooperate first, your partner sees what you did, then he decides to defect or cooperate. If he sees that you cooperated without a doubt, that might be enough for him to cooperate as well. Our model now looks like this

The poorly made tree above describes the situation where 1 is interrorgated first, decides to defect or cooperate, 2 sees what 1 did, then 2 is interrorgated and decides to either defect or cooperate. Let’s say you cooperate. Unfortunately, evening knowing that, 2 still won’t cooperate with you; he will defect. It doesn’t matter than 2 knows your loyal. To him, its a choice between 1 life sentence and 0 life sentences. He’s gonna choose 0.

This whole defect thing is seeming pretty convincing, but let’s not give up yet. There’s still more ways we can think about this 10.

We’ll meet again

Recall from the aside that there are other examples of prisoner’s dilemas than this somewhat literal scenario. If you both defect (or both cooperate), you’ll both end up in jail. Certainly, you will interact with each other again, and in doing so, you will likely end up in other prisoner’s dilemas in the future11 albeit less literal ones. With this in mind, maybe if you both cooperate now, you will be willing to continue cooperating in the future since its better than both of you defecting. This could be what we need to give justification to our intuition.

Let’s say the two of you will experience \(k\) prisoner’s dilemas in total (no matter what choice you make in any of them). At each dilema, you both aquire some payoff described according to the numbers in our original payoff matrix12. At the end of the \(k\) dilemas, your payoff is the sum of all the payoffs you received during the individual dilemas, and this is the quantity you want to maximize. For your convience, the payoff matrix is reproduced below.

\[\begin{array}{l | c | r |} & C & D\\ \hline C & 2,2 & 0,3 \\ \hline D & 3,0 & 1,1 \\ \hline \end{array}\]Choose \(k\) arbitarily. Let’s say you’ve both agreed to always cooperate. Can we reasonably expect that this is what we’ll do, or will we have some incentive to deviate from this strategy. It may be hard to think about this by imagining all \(k\) dilemas at once, so let’s say you are on the \(k^\text{th}\) dilema. You’ve come accross \(k-1\) dilema situations with your partner, and every single time, you both cooperated. Things are going fairly well. This is your last dilema together; clearly, you should cooperate again, right? Wrong. It’s the same argument as always. If you are so sure your partner will cooperate, then it’s in your best instance to defect!

But wait, that was just for the last dilema. Maybe you too can still cooperate up until then; play nice in the beginning to gain your partner’s trust, only to backstab him in the end. If only this could work. Your partner can reason the same way and so you will both conclude that the other one will turn on you and defect in the end. Once you realize there’s no point in cooperating the first \(k-1\) times (since it won’t convince your partner to cooperate the \(k^\text{th}\) time), your only choice left is to defect the \((k-1)^\text{th}\) time, and cooperate at most \(k-2\) times. Unfortunately, this line of reasoning can be repeated again and again, resulting in both of you defecting every single time, and this is true no matter what value of \(k\) you pick. So it seems even if you meet again, you really can’t be convinced it’s worth while to cooperate with this guy.

When is the last time, though?

The argument above all stemmed from one fact. No matter how much you cooperate, when you finally reach the end of it all, you’re gonna want to defect. This argument contains one perculiarity though; it implicitly assumes that you know when your last dilema is. I don’t know about you, but I can’t predict the future. When I interact with people, I can’t say for sure if it’s the last time we’ll interact or not. Certainly, it seems strange to use a model where people have these incredible powers of foresight. So, what model do we use now?

Our previous observation that future interactions can cause you to want to cooperate still seems reasonable to me. Last time, it went wrong because eventually you knew you had no more future interactions, and then everything unwound from there, but like we said, in the real world you could always potentially have more interactions down the line. To model this, instead of saying you face \(k\) dilemas in total, you and your partner will face infinitely many dilemas together. We’re trying to keep things realistic here, and this fails on at least two accounts. 1.) You never interact with anyone inifintely many times in the real world. 2.) When you interact with someone, you may not know how many more times you will, but you’re probably more confident that it will happen (at least) once more than that it will happen (at least) 10,000 times more. To address these, we will introduce a discount factor \(\delta\)13 where \(0<\delta<1\). This number can be thought of a measure of how patient you are, how likely it is that your current dilema is not the last one, etc.

Now let’s explicitly say what our latest model is. You and your partner play infinitely many prisoner’s dilemas, and at each one, you have the same possible actions (defect or cooperate) and the same payoffs (given by the matrix somewhere above). For each dilema, you play it like normal (moving simultaneously), and receive some payoff. Previously, your goal was the maximize the sum of all your payoffs. Here, your goal is the maximize the discounted sum of your payoffs. Letting \(u_t\) be your payoff from the \(t^\text{th}\) dilema, the quantity you are trying to maximize is

\[\begin{align*} \sum_{t=0}^\infty\delta^tu_t \end{align*}\]We can’t use the same argument from before to say that you will both defect every time since that argument depended on having some last interaction to start (and argue backwards) from. So far, so good. Let’s say you both agreed beforehand to always cooperate. Do you still have incentive to start defecting? The answer is\(\dots\) of course you do. Think about it. You both agreed to always cooperate, so you can be confident your partner will always cooperate. If that is the case, you should always defect instead, and you will get a strictly higher payoff (independent of the value of \(\delta\)). Your partner can use this reasoning too, and so it is still reasonable to expect both of you to always defect.

That argument makes sense, but it really only makes sense if you expect your partner to cooperate no matter what. That isn’t a very likely thing. So, let’s not give up; let’s change our strategy. Instead of agreeing to always cooperate, you and your partner agree to always cooperate with the stipulation that if one of you ever defects, then you both start defecting from their on. Like before, if you both follow this strategy, you will both always cooperate. However, now if one of you deviates, he won’t be forever rewarded with strictly higher payoffs. He’ll have exactly one instance where his payoff is higher than before (3 instead of 2), and infinitely many where its lower than before (1 instead of 2). Is that it? Have we finally found justification for our intuition? I mean, there’s no way one instance of higher payoff is worth infinitely many instances of lower payoff, right? right? Well\(\dots\)

Infinite is certainly bigger than 1, but we’re not maximizing the outright sum of individual payoffs, but the discounted sum of payoffs. Certainly, if \(\delta=0\), we would still want to defect in the original dilema since it would be the only one giving us any payoff14. \(\delta\) can’t be 0, but it can be close to zero. You would imagine that for small enough \(\delta\), this reasoning still (essentially) holds, and we conclude that you should in fact still defect. It’s possible that this is true for all \(\delta\) (or at least for fairly large \(\delta\), like 0.95) and that would mean that, unless you were very patient or very certain you will keep on seeing this guy, you should still defect.

The only way to know for sure if this model gives satisfying results is to figure out what for which values of \(\delta\) you should always cooperate. Certainly, if someone defects somewhere along the way, then you should always defect from there on out. No matter what \(\delta\) is, once someone has defected, you expect your partner to always defect, and so it makes no sense for you to decrease your payoff by cooperating. Thus, the only thing we need to consider in our analysis is if it is ever a good idea to defect in the first place. Fix any \(T\), and imagine you defect for the first time at time period \(T\). Let’s compare what happens when you always conform to your agreed upon strategy and what happens when you deviate at time \(T\) by defecting.

\[\begin{matrix} \text{conform:} & (C, C) & (C,C) & \dots & (C, C) & (C, C) & (C, C) & (C, C) & \dots\\ \text{deviate:} & (C, C) & (C,C) & \dots & (D, C) & (D, D) & (D, D) & (D, D) & \dots \end{matrix}\]If you conform, you both always cooperate. If you deviate at \(T\), then you both cooperate for a while, then you defect while your partner cooperates, then you both defect forever. You will only want to deviate if it increases your payoff, so let’s look at the payoffs from coforming and from devating. If you conform, your payoff is

\[\begin{align*} \sum_{t=0}^\infty2\delta^t=\frac2{1-\delta} \end{align*}\]However, if you deviate, your payoff is

\[\begin{align*} \sum_{t=0}^{T-1}2\delta^t + 3\delta^T + \sum_{t=T+1}^\infty\delta^t =\frac{1-2\delta}{1-\delta}+\frac2{1-\delta} \end{align*}\]You only want to deviate if your payoff is higher, so you will only deviate when \(\delta\) satisfies the following.

\[\begin{align*} \frac{1-2\delta}{1-\delta}>0 \iff 1-2\delta>0 \iff \delta<\frac12 \end{align*}\]Which means you will want to always cooperate if \(\delta\ge\frac12\)15! Finally, true justification for our intuition. This essentially says that if your at least as patient as average 16, then you want to cooperate, which makes sense. You wouldn’t really expect a short-sided person to want to cooperate, but you would expect someone willing to wait for future benefit to.

Some Thoughts

The Prisoner’s Dilema – and more generally, the type(s) of reasoning we touched upon here – come from a field known as Game Theory. Basically, game theorists study how rational beings should behave in different situations. There’s way more to game theory than just this prisoner’s dilema, and many more types of models of games than I introduced here.

This quarter I am taking ECON 180: Honors Game Theory. Before starting the class, I knew very little about game theory. I had heard of the subject (and it seemed interesting), and I had watched a few online lectures of a game theory course at Yale. From what little I had seen, I had the idea that game theorists studied only simple models (like the first one we had here), and that they only searched for Nash Equilibrium17, which didn’t always match up with intuition or accurately predict human behavior. Don’t get me wrong. I expected that there was more to this, and wanted to learn the deeper theory behind it all; I was just not completely convinced the theory was very deep. Certainly, I did not expect to come across even just the different types of models (informally) used in this post. Through this class, I have found that game theory is a much deeper field than I expected, and have even entertained the thought of taking more classes in it, and possibly making it the focus of my studies. I’ve discovered that Nash equilibria aren’t the only equilibria18, that this field has more history than I thought19, that almost any situation is a game20, etc.

I was reminded of this yesterday during class. A little bit of context: I was not feeling like going to class. I was super tired, I had just come off a break and was overall less motivated to get work done, it’s an almost 2 hour long class, I wanted some food, etc. Honestly, the main thing that caused me to go was that I needed to turn in a problem set. But class started, the professor had written on the board what we would be talking about that day, and my attitude instantly changed. We were going to be talking about learning and evolution. At the beginning of this quarter, he had mentioned that we would cover this towards the end of the quarter, and I had been looking forward to it ever since.

For a little bit of context, my current future goals lie in AI. I hope to one day some sort of research in artificial intelligence, and specifically, machine learning, so the topic vibed with me. Not only that, but throughout the course, many times we’ve gone over something that reminded me of reinforcement learning. The idea of players trying to take actions to maximize a payoff functions often had parallels with the idea of an agent trying to take actions to maximize future reward in an environment. Every time I was reminded of this seeming connection, I would make a mental21 note to do some investigating of it on my own, to write some programs where 2 RL agents repeatedly play a game and see if their strategies converge to nash equilibrium, for example. However, I never went through with these plans; they always just lied dormant on my mind and on my paper. Sitting in class yesterday, finally talking about learning in game theory, I kept on thinking about what I had gained from this class, what I wanted from this class that I forgot to pursue, and what, if any, insights I can gain from exploring parallels between game theory and RL.

There’s no lesson I’m trying to convey with this. It’s just something on my mind.

-

Note: I know basically nothing about the legal system and crime and justice and how it all (attempts to) work together. Just go along with me here, and pretend everything I’m saying makes sense and is as it should be. ↩

-

Here, these are life sentences with the possibility for parole after a few decades (depending on how many you get) of good behavior. ↩

-

I think this is a Prisoner’s Dilema, but I haven’t put enough thought into it yet to confirm that. I think it will be more clear if I just lied or not after the next section ↩

-

And this is my blog, so we do whatever I want ↩

-

table? ↩

-

From here on, I’ll use player to refer to you or your crime mate. You can be player 1 and he’ll be player 2. ↩

-

Defecting strictly dominates cooperating ↩

-

What has he every done for you anyways, other than help commit a crime that might land you in jail for the rest of your life? ↩

-

maybe its maybelline ↩

-

At this point, having spent longer than I would like to admit making the above (admittedly not very high quality) graphic, I decided to call it a night, and continue writing tomorrow. This is the first time I have split writing a single post between two days. I’m curious to see if I remember to include everything I wanted to after spending so much time away from it. ↩

-

This is still possibly true even if one you defects while the other cooperates. ↩

-

Previously, we interpreted these numbers in terms of life sentences. That now only makes sense for the first dilema. Future dilema’s you two face may have nothing to do with jail time. Nevertheless, your payoffs can be assigned these same values because what matters is the relationship between the numbers, and not their specific values. ↩

-

delta ↩

-

here, we’re using the convention that 0^0=1 ↩

-

and you and your partner agreed upon this specific strategy, either explicitly or implicitly, beforhand. ↩

-

assumint patience is, for example, distributed uniformly from 0 to 1 ↩

-

Situations in simultaneous games where everyone is doing the best thing given their opponent’s action. One example is, perhaps unsurprisingly, both players defecting in the prisoner’s dilema. ↩

-

In fact, there are too many of them. In class so far, we’ve talked about nash equilibria, subgame perfect equilibria, bayesian nash equilibria, weak perfect bayesian equilibria, and sequential equilibria. These aren’t even all of them. Not even close, I think. ↩

-

There were people doing game theory in at least the 1800s. I always assumed it was something that got start in the early or mid 1900s. ↩

-

I’ve started a habit of relating things in my daily life to games from class ↩

-

and sometimes physical ↩