I think this is going to end up being a long one 1, and it possibly won’t be the easiest post to follow; mostly because I will likely end up introducing a decent number of topics I haven’t talked about here before. I guess we’ll see how things turn out 2.

Historically, one topic of interest to number theorists has been diophantine equations. The are equations where you are looking for integer solutions. One famous example is \(a^2+b^2=c^2\) where you look for integer solutions. In general, there’s no overarching method to solve any diophantine equation 3, and so individual equations may be solved using ad hoc seeming methods. For example, the pythagorean equation can be solved by projecting points from the unit circle onto a line 4. Another (class of) well-known example(s) is due to Fermat: \(a^n+b^n=c^n, n>2\), but we’ll put off solving this one until a later post.

This post is all about solving Pell’s equation (here, of course, \(x,y,\) and \(d\) are integers)

\[\begin{align*} x^2-dy^2 = 1 && d>1 \end{align*}\]Question

Why do we require \(d>1\)? What happens if \(d\le1\)?

Edit

I never mentioned this in the original post 5, but we also want to assume that \(d\) is not a square number. If \(d=k^2\), then the equation becomes \((x-ky)(x+ky)=1\) which means \(x+ky=x-ky=\pm1\) so \(ky=-ky\implies y=0\) and \((x,y)=(\pm1,0)\) are the only solutions.

A Warm-up Problem: \(y^2=x^3-2\)

Before solving Pell’s equations, we’ll start with a simpler task (although it may not be immediately obvious that this equation is any easier to solve). At this point, if it seems like things here will be really novel to you, then I recommend that you check out my previous post on number theory. It’s not required to understand this post, and won’t necessarily add a bunch to your knowledge of the ideas used here, but I think it could serve as good motivation for seeing that both geometric reasoning and working in number systems larger than \(\Z\) can be helpful in tackling number theoretic problems 6.

If you were to decide to stop reading, leave this post, and go start finding and solving diophantine equations, one thing you will notice is that multiplication makes things so much easier.

Mini warmup

\(\begin{align*} &x^2+6xy+5y^2=10\\ \implies &(x+5y)(x+y) = 10\\ \implies &x+y=2, x+5y=5 &or& &x+y=5, x+5y=2 &&or\\ &x+y=-2, x+5y=-5 &or& &x+y=-5, x+5y=-2\\ \implies &2+4y=5 &or& &5+4y=2 &&or\\ -&2+4y=-5 &or& &-5+4y=-2\\ \implies &y=\pm\frac34 \end{align*}\)

Hence, this particular diophantine equation has no solutions.

If you can set your problem up as one thing times another thing equals a third thing, then since everything is an integer, the things on the left hand side must be factors of the right hand side! This vastly reduces the number of potential solutions 7, and often can lead directly into an actual solution (ot show that non exist).

That being said, the key insight to solving our warmup problem is that we can rewrite it as \(y^2+2=x^3\). I’ll take a second to pause so you can let out a gasp 8 of amazement. Once things are in this form, we can see that the left hand side is almost a difference of squares. The only problem is that it’s not a difference and \(2\)’s not a square, but motivated by the possibility of factoring the left hand side, we ignore these constraints, stop restricting ourselves to \(\Z\), and from here on out, do our work in \(\zadjns2=\{a+b\sqrt{-2}\mid a,b\in\Z\}\) instead 9. I don’t know if this feels illegitamate, but it shouldn’t because it’s not, so I’m gonna move on.

We can now write our equation as \((y+\sqrt{-2})(y-\sqrt{-2})=x^3\). At this point, we really hope that \(y\pm\sqrt{-2}\) are coprime so that they must both be perfect cubes; this would be a fairly restrictive condition. However, hoping this would be getting ahead of ourselves. This line of thinking would work in \(\Z\), but the reason it works (and the reason we can have a sensible definiton of coprime in the first place) is because \(\Z\) is a unique factorization domain 10, but we’re working with \(\zadjns2\) instead of just \(\Z\). Luckily, it turns out that this is a UFD as well, but this is a non-trivial claim that could have failed if we had added a different square root instead 11.

Exercise

Show that \(\zadjns2\) is a UFD.

Hint: It suffices to show that it’s a Euclidean domain, and you can do this by considering points closest to the “ambient quotient” 12. Also, you might want to read ahead a little before tackling this exercise.

To show that \(y\pm\sqrt{-2}\) are coprime, we’ll introduce a norm.

Definition

Given \(x+y\sqrt{-2}\in\zadjns2\) with \(x,y\in\Z\), it’s norm is \(N(x+y\sqrt{-2}):=(x+y\sqrt{-2})(x-y\sqrt{-2})=x^2+2y^2\)

This definition should look familar to anyone who read my previous post, and so it should not come as a surprise that this norm is multiplicative. That is, for any \(x,y\in\Z[\sqrt{-2}]\), we have \(N(xy)=N(x)N(y)\). Let \(p\in\Z[\sqrt{-2}]\) be a common factor of \(y\pm\sqrt{-2}\); this means that \(p\mid(y+\sqrt{-2})-(y-\sqrt{-2})\) so \(p\mid2\sqrt{-2}=-(\sqrt{-2})^3\).

Before proceeding, a quick note. When considering factoring and related concepts (like primality), we don’t care about units (numbers dividing 1) because units are annoying and change nothing. Furthermore, a number \(x\in\zadjns2\) is a unit iff \(N(x)=1\). Proving this is left as an exercise to the reader.

Now, back to our problem. The following proposition implies that \(p=u\sqrt{-2}^e\) for some unit \(u\in\Z[\sqrt{-2}]\) and integer \(0\le e\le 3\).

Proposition

In \(\zadjns2\), \(\sqrt{-2}\) is prime 13.

While we’re on the subject

Exercise

Show that the only units in \(\Z[\sqrt{-2}]\) are \(\pm1\).

Returning to showing that those two numbers are coprime, we can now safely conclude that \(p=u\sqrt{-2}^e\) with \(u,e\) as described above. Hence, either \(p\) is a unit (in which case we win) or \(\sqrt{-2}\mid p\), so let’s assume the latter. This then means that \(\sqrt{-2}\mid y+\sqrt{-2}\). So, for appropriately chosen integers \(u,v\), we have

\[\begin{align*} y+\sqrt{-2} = \sqrt{-2}(u+v\sqrt{-2}) &= -2v + u\sqrt{-2} \\ &\implies y = -2v \end{align*}\]Finally, the following proposition shows that this is impossible so \(p\) must be a unit, and hence \(y\pm\sqrt{-2}\) are coprime.

Proposition

If \((x,y)\in\Z^2\) satisfies \(y^2=x^3-2\), then \(y\) is odd.

Now we’re almost there. We know that \(y+\sqrt{-2}\) and \(y-\sqrt{-2}\) are coprime, and that their product is \(x^3\). It follows from unique factorization that \(y+\sqrt{-2}\) must the product of a unit and a cube. However, you showed that the only units are \(\pm1\), so \(y+\sqrt{-2}=(a+b\sqrt{-2})^3\) for some integers \(a,b\). We can expand things to get

\[\begin{matrix} & y+\sqrt{-2} &=& (a^3-6ab^2)+\sqrt{-2}(3a^2b-2b^3)\\ \implies & 1 &=& 3a^2b-2b^3 &=& b(3a^2-2b^2)\\ \implies & \pm1 &=& b\\ \implies & \pm1 &=& 3a^2 - 2\\ \implies & 2\pm1 &=& 3a^2\\ \implies & \pm1 &=& a\\ \implies & 1 &=& b \end{matrix}\]I didn’t feel like explaining all those implications, but the moral of the story is that we have two solutions given by \((a,b)=(\pm1, 1)\) which correspond to \(y+\sqrt{-2}=(1+\sqrt{-2})^3=-5+\sqrt{-2}\) and \(y+\sqrt{-2}=(-1+\sqrt{-2})^3=5+\sqrt{-2}\). Both of these solutions for \(y\) corresponsd to \(x=3\), so our original equation has two solutions: \((x,y)=(3,\pm5)\).

Introduction to Algebraic Integers

Now that the warmup is done, we can start building all the theory we’ll need to solve Pell’s equations. The first thing we’ll need is the so-called ring of integers. As the warmup demonstrated, it’s often helpful to work in “large” systems of numbers instead of the relatively small \(\Z\). However, it may not always be clear what group of numbers is the right one for a problem. To answer this question, we focus our attention on algebraic integers. The idea is that regular integers are a particular, nice subset of the field \(\Q\) of rational numbers 14, and so the right systems of numbers to work with are analagous nice subsets of fields bigger than \(\Q\). Because we’re doing algebra, and algebraists love little more than polynomials, the characterization of nice will be done in terms of a polynomial condition inspired by the rational root theorem. With all of that said, let’s see some definitions

Definition

A number field \(K\) is a finite field extension 15 of \(\Q\). Furthermore, if \(K\) is of the form \(K=\Q(\sqrt d)=\{a+b\sqrt d\mid a,b\in\Q\}\) for squarefree \(d\in\Z\), then \(K\) is called a (real or imaginary) quadratic number field.

Number fields play the role of \(\Q\) in the big picture. From these, we extract nice subsets of so-called algebraic integers.

Definition

An algebraic integer \(x\) is a root of a monic polynomial 16 \(f\in\Z[X]\) with integer coefficients. Given a number field \(K\), it’s ring of integers \(\ints K\) 17 is the set of algebraic integers in \(K\).

If this definition, seems weird, then maybe the next exercise will help you see why it’s actually reasonable. If that doesn’t work, then try to come up with another definition that’s well-defined for any number field and makes sense in the case of \(\Q\).

Exercise

Show that \(\ints\Q=\Z\).

Because of this exercise, mathematicians sometimes refer to \(\Z\) as the ring of “rational” integers in order to distinquish it from other rings of integers. Also, I keep calling these things rings, but it is in no way obvious that they actually do form rings (go ahead and try to prove that \(ab\) and \(a+b\) are algebraic integers if \(a,b\) are. I won’t cover the proof here, but the secret is Cramer’s formula).

For the purposes of this post, we’ll only need to study quadratic number fields, but it’s worth noting that number fields in general – and even arbitrary finite field extensions – have a norm.

Definition

Given a finite field extension \(L/K\), let \(\alpha\in L\) be an arbitary element. Note that \(\alpha\) induces a map \(m_\alpha:L\rightarrow L\) given by multiplication \(m_\alpha(\beta)=\alpha\beta\), and that \(m_\alpha\) is \(K\)-linear. We define the norm of \(\alpha\) to be the determinant of this map. That is, the norm is a map

This definition is quite a bit to digest, but we’ll unpack it in the case of quadratic number fields. One thing of note we can quickly gleen from this definition is that it makes the statement that the norm is multiplicative almost trivial (why?).

Now, let’s see what this definition gives in the quadratic case. Fix some squarefree \(d\in\Z-\{1\}\), and let \(K=\Q(\sqrt d)\) so \(K/\Q\) is a degree 2 18 field extension, and one \(\Q\)-basis of \(K\) is \(\{1,\sqrt d\}\). Fix any element \(\alpha=a+b\sqrt d\) of \(K\) with \(a,b\in\Q\). We are interested in the determinant of its multiplication map, so we’ll first find the matrix for this map. To do this we only need to compute \(m_\alpha(1)=\alpha=a+b\sqrt d\) and \(m_\alpha(\sqrt d)=\alpha\sqrt d=db+a\sqrt d\). Hence, the \(m_\alpha\) is given by this matrix (assuming we use the basis \(\{1,\sqrt d\}\)):

\[\begin{pmatrix} a & db\\ b & a \end{pmatrix}\]Thus, \(\knorm(a+b\sqrt d)=a^2-db^2\) which turns out to also be \((a+b\sqrt d)(a-b\sqrt d)\) 19. The fact that this norm takes this multiplicative form means the following theorem is really easy to prove in the quadratic case 20.

Theorem

Let \(K\) be a quadratic number field. Then, \(\alpha\in\ints K\) is a unit (in \(\ints K\), not \(K\). \(K\) is a field so basically everything is a unit) if and only if \(\knorm(\alpha)=\pm1\)

(\(\leftarrow\)) Coversely, assume \(\knorm(\alpha)=\pm1\). As the above discussion noted, \(\knorm(\alpha)\) is a product of two numbers, so this says exactly that \(\alpha\) is a unit. \(\square\)

The diligent reader will be somewhat bothered by the above proof. That’s because it implicitly relies upon something I forgot to prove first, which is the following (where does the above proof rely on this theorem?).

Theorem

Let \(K\) be a quadratic number field. Then, \(\knorm(\ints K)\subseteq\ints\Q\) which is to say that the norm of an algebraic integer is a rational integer 21.

Now, one last thing, and then we’ll say how all of this discussion on integers and norms relates to Pell’s equations 22. I’ve tried to be careful so far to be conscious of the fact than a priori, an elment of \(\ints K\) could look like a general member of \(K\) in the sense that it’s coefficients could be general rational numbers. From here on out, we’ll be a little more concrete because we’re going to actually compute \(\ints K\) in the quadratic case.

Theorem

Let \(K=\Q(\sqrt d)\) be a quadratic number field with \(d\in\Z-\{1\}\) a product of distinct primes (i.e. square free). Then,

Case 1: $$x\in\Z$$

We also know that $$\knorm(\alpha)=\alpha\conj\alpha=x^2-dy^2\in\Z$$ so by taking a difference, this means that $$dy^2\in\Z$$. This means that $$y\in\Z$$. If it were not, then the denominator of $$y^2$$ would be divided by some prime $$p$$ more than once. However, $$d$$ is divisible by $$p$$ at most once, so the product $$dy^2$$ would contain a $$p$$ in the denominator and hence not be an integer. Thus, $$\alpha\in\Z[\sqrt d]$$.

Case 2: $$x=\frac n2$$ for some odd $$n\in\Z$$

Once again, $$\knorm(\alpha)=x^2-dy^2=n^2/4-dy^2\in\Z$$. Note that $$y\not\in\Z$$ since otherwise we would have $$n^2/4\in\Z$$. Counting prime factors again shows us that we must have $$y=m/2$$ for some odd $$m\in\Z$$ which means that $$n^2-dm^2\equiv0\pmod4$$ with $$n^2,m^2\equiv1\pmod4$$ so $$d\equiv1\pmod4$$. Hence, $$\alpha=n/2+m\sqrt d/2=(1+\sqrt d)/2+(n-1)/2+\sqrt d(m-1)/2\in\Z[(1+\sqrt d)/2]$$ since $$\sqrt d=2(1+\sqrt d)/d - 1\in\Z[(1+\sqrt d)/2]$$

Corollary

\(\ints{\Q(\sqrt{-2})}=\Z[\sqrt{-2}]\) so this was the right setting for the warmup problem.

At this point, I think we know everything about rings of integers that we’ll need 23. In case you have forgotten, our goal is find all integer solutions to Pell’s equations which are \(x^2-dy^2=1\) for integers \(x,y\in\Z\) and positive integer \(d\in\Z_{>1}\). As this discussion hinted at, for the time being, we’ll further restrict \(d\) to be square free. This has the advantage that since Pell’s equation can then be written as \((x-y\sqrt d)(x+y\sqrt d)=1\), \(d\) which means that we’re really just looking for units of \(\Z[\sqrt d]\), which is convenient because \(\Z[\sqrt d]=\ints{\Q(\sqrt d)}\) for square free \(d\) (or at least it is 2 times out of 3) 24.

Geometry of Numbers

I debated whether I should talk about what comes next in one section or two. I ultimately decided on two because I didn’t want to introduce too much stuff all at once. A priori, the material of this section isn’t relevant to the larger discussion at hand, but in the next section, we’ll see it play a crucial role. This is the point in the post where we open up to the possibility of me throwing in some pictures.

Definition

A lattice of a real vector space is the \(\Z\)-span of some \(\R\)-basis. If \(L\) is a lattice of a real vector space \(V\), then we say the rank of \(L\) is the dimension of \(V\) 25.

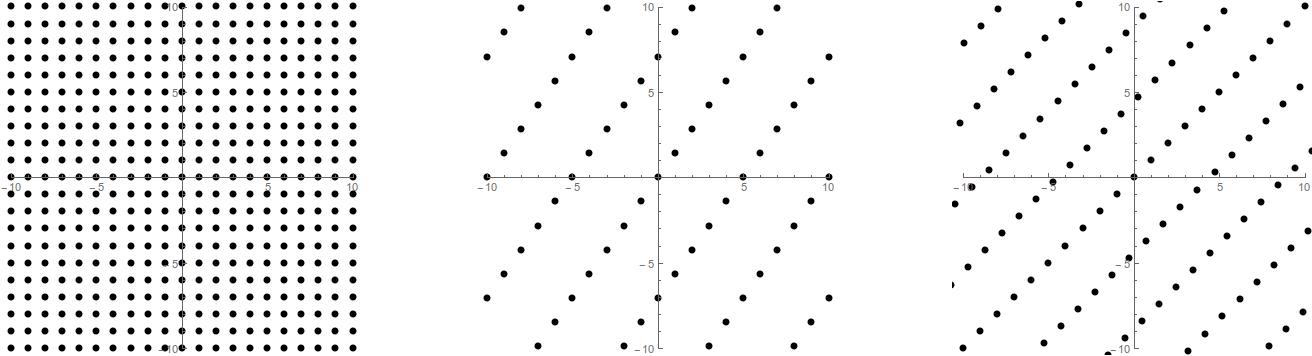

The only (finite-dimensional) real vector spaces are \(\R^n\) for various choices of \(n\), so a lattice is really just a set of the form \(\{a_1b_1+a_2b_2+\dots+a_nb_n:a_1,\dots,a_n\in\Z, b_1,\dots,b_n\in\R\}\) and the \(b_i\)’s are \(\Z\)-linearly independent. We might write such a lattice using the notation \(L=\Z b_1\oplus\Z b_2\oplus\dots\oplus\Z b_n\) 26. The canonical example (and in some sense only (finite) example) of a lattice is \(\Z^n\). Some lattices of \(\R^2\) are pictured below

One property of lattices that will come up is that they are discrete.

Definition

A subset \(D\subset\R^n\) is called discrete if only finitely many of its points are contained in any bounded region. That is, it is discrete if \(D\cap B_r\) is finite for all \(r\in\R\) where \(B_r\) is the (solid) ball of radius \(r\) centered at the origin.

I won’t give a full, formal proof that all lattices are discrete, but I will sketch one direction you could take. The idea is that in a lattice, there exists some \(\eps>0\) such that any two lattice points are a distance greater than \(\eps\) apart. So, if you have some bounded set \(B\), you can split it up into finitely many balls \(B_{\frac{\eps}2}\) of radius \(\eps/2\). Each of these contains at most 1 lattice point, so \(B\) contains a finite number of lattice points.

Now, lattices are discrete and look a lot like \(\Z^n\), so it’s natural to think that have some connection with numbers27. Because of this, and because they have applications in number theory, some results on or relating to lattices form the so-called geometry of numbers. Here, we’ll prove and use one such theorem, but before that, we need to describe the volume of a lattice.

Definition

Let \(\Gamma\) be a lattice in \(\R^n\). Then, we say the volume \(\vol_{\Gamma}\) of \(\Gamma\) is the volume of a parrallelogram 28 spanned by a \(\Z\)-basis of \(\Gamma\).

Examples

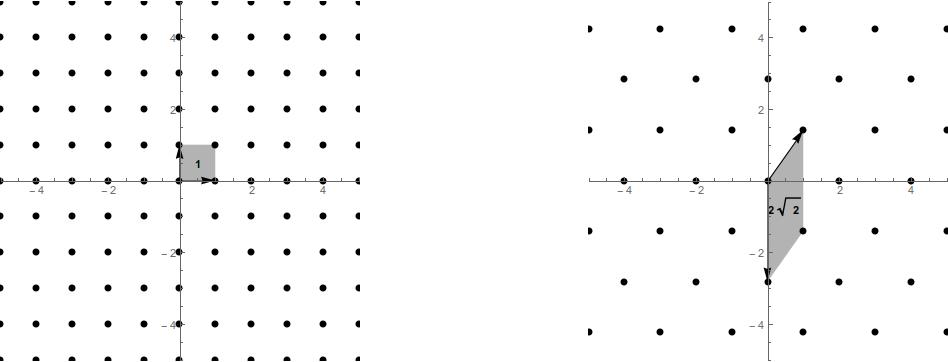

The standard lattice \(\Gamma_1=\Z^2=\Z(1,0)\oplus\Z(0,1)\) has volume \(\vol_{\Gamma_1}=1\) since the basis \(\{(0,1),(1,0)\}\) spans a unit square.

The lattice \(\Gamma_2 = \Z(1,\sqrt2)\oplus\Z(0,-2\sqrt2)\) has voluem \(\vol_{\Gamma_2}=2\sqrt2\)

I know what you’re thinking. What if I choose a different basis for my lattice? Instead of writing \(\Z^2=\Z(1,0)\oplus\Z(0,1)\), I might want to write \(\Z^2=\Z(2,-1)\oplus\Z(-3,1)\). Well, doesn’t matter.

Theorem

The volume of a lattice is well-defined.

Now, a couple definitions just to make sure everyone is on the same page, and then the main theorem.

Definitions

Fix some subset \(D\subseteq\R^n\).

We say \(D\) is compact if it is closed 29 and bounded.

We say \(D\) is convex if any line between points in \(D\) is contained in \(D\). That is, for any \(a,b\in D\) and \(t\in[0,1]\), the point \(at+b(1-t)\in D\).

Fixing some point \(o\in\R^n\), we say \(D\) is symmetric about \(o\) if for all \(p\in D\), we also have \(o-p\in D\).

- A ball is compact, convex, and symmetric about it’s center

- A sphere is compact and symmetric about it’s center, but not convex

- A triangle is compact and convex, but not symmetric about any point

- The inside of a ball is convex and symmetric about it’s center, but not compact

- A five-pointed star is compact and convex, but not symmetric about any point

- A line segment is compact, convex, and symmetric about it’s center

- An infinite line is convex and symmetric about many points, but not compact

Minkowski Convex Body Theorem

Let \(\Gamma\) be a lattice in \(\R^n\), and \(D\subseteq\R^n\) be compact, convex, and symmetric about the origin. Furthermore, assume \(\vol(D)\ge2^n\vol_\Gamma\). Then, \(\Gamma\cap D\neq\{0\}\).

The idea behind the proof is that \(D\) is just too big to miss all of \(\Gamma\). You essentially take a big parralellogram spanned by a basis of \(\Gamma\) and tile \(\R^n\) with it. After that you move all the pieces touching \(D\) back to the original piece about the origin, and if the volume of \(D\) is greater than the volume of the original piece, then two points of \(D\) must end up at the same point of the parallelogram. This means that their difference must be twice a lattice point, so their midpoint is a lattice point.

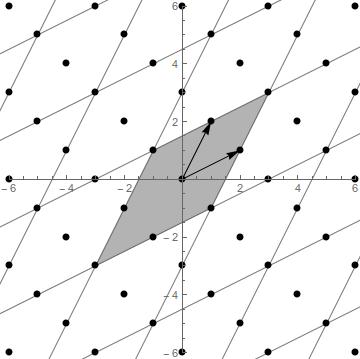

I wasn’t sure what the best way to visualize this without it being a mess was, so here’s a picture of the parralellogram to keep in mind. You can add in \(D\) and whatnot using your imagination.

If you follow the sketch above, in the end, it relies on \(D\) have strictly greater volume, but the theorem doesn’t. This is reconciled by the following.

Lemma

If Minkowski’s theorem holds for all \(D\) with \(\vol(D)>2^n\vol_\Gamma\), then it holds for all \(D\) with \(\vol(D)=2^n\vol_\Gamma\) as well.

Awesome, now we handle the main theorem with the further assumption that \(D\) has strictly greater volume.

Real Embeddings of Quadratic Number Fields

Now we know some things about about quadratic number fields, and we know a little about the geometry of numbers, so let’s put the two together. The bridge between abstract fields and more concrete geometric ideas will be embeddings.

Definition

A real embedding of a number field \(K\) is a ring homomorphism 30 \(K\hookrightarrow\R\).

If you’ll recall, in Pell’s equations, we have some \(d>1\), so consider such a \(d\) and a number field \(K=\Q(\sqrt d)\). This field has 2 real embeddings. An embedding is determined by where it sends \(1\) and \(\sqrt d\) (why?), but \(1\) must map into \(1\). However, \(\sqrt d\) has two possible images corresponding to the two solutions to \(x^2-d=0\). In fact, if \(\sigma:K\hookrightarrow\R\) is an embedding, then \(\sigma(x^2-d)=\sigma(x)^2-d\) so \(\sigma(\sqrt d)^2-d=\sigma((\sqrt d)^2-d)=\sigma(0)=0\). This is all to say that a real quadratic field has two real embeddings. Because these are equivalent as far as algebra is concerned, instead of choosing one arbitarily, we’ll make use of both. Define the function 31

\[\begin{matrix} \iota: &K &\longrightarrow& \R^2\\ &\alpha &\longmapsto& (\alpha, \conj\alpha)\\ &a+b\sqrt d &\longmapsto& (a+b\sqrt d, a-b\sqrt d) && a,b\in\Q \end{matrix}\]Theorem

For a real quadratic number field \(K\), \(\iota(\ints K)\) is a lattice.

A natural question to ask is what is the volume of \(\iota(\ints K)\)? Once again, fix some square free \(d>1\) and let \(K=\Q(\sqrt d)\). Then,

\[\begin{matrix} \vol_{\iota(\ints K)} &=& \begin{vmatrix} \iota(1) \\ \iota(\sqrt d) \end{vmatrix} &=& \begin{vmatrix} 1 & 1\\ \sqrt d & -\sqrt d \end{vmatrix} &=& |-2\sqrt d| &=& 2\sqrt d && \text{if }d\equiv2,3\pmod4\\ \vol_{\iota(\ints K)} &=& \begin{vmatrix} \iota(1) \\ \iota\left(\frac{1+\sqrt d}2\right) \end{vmatrix} &=& \begin{vmatrix} 1 & 1\\ \frac{1+\sqrt d}2 & \frac{1-\sqrt d}2 \end{vmatrix} &=& |-\sqrt d| &=& \sqrt d && \text{if }d\equiv1\pmod4 \end{matrix}\]Motivated by this calculation, we make the following definition

Definition

The discriminant of a real quadratic number field \(K=\Q(\sqrt d)\) is \(4d\) if \(d\equiv2,3\pmod4\) and \(d\) if \(d\equiv1\pmod4\). Depending on how we feel, we may denote this \(\disc(K), \zdisc(\ints K),\) or \(D_K\).

Note that \(\vol_{\ints K}:=\vol_{\iota(\ints K)}=\sqrt{\zdisc(\ints K)}\). Furthermore, the following is a neat result 32

Theorem

If \(K=\Q(\sqrt d)\) is a real quadratic number field, then

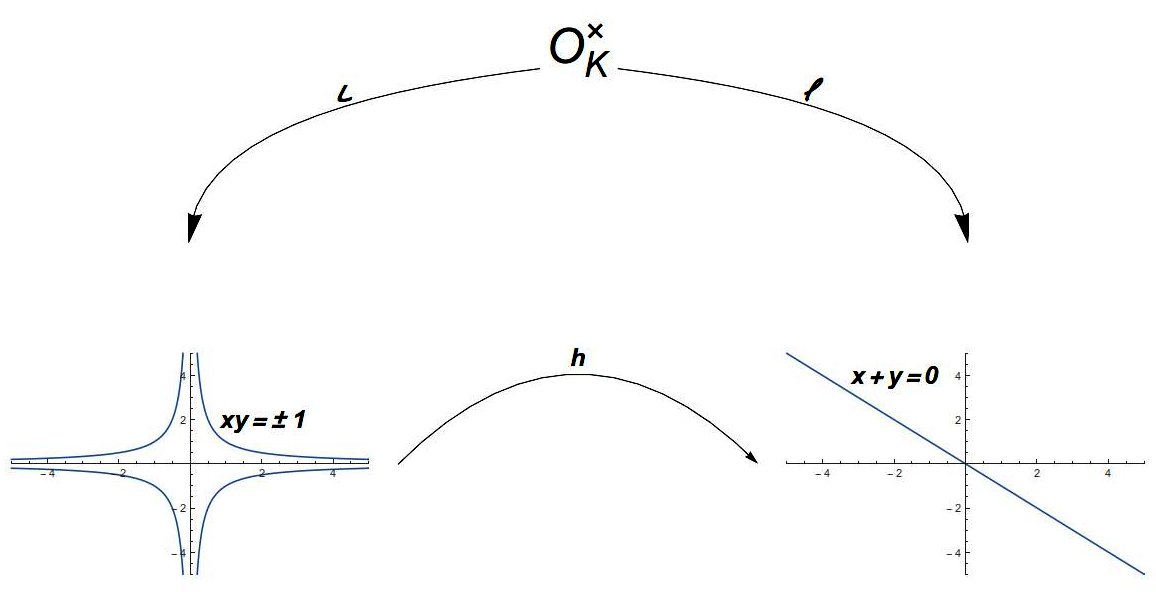

Recall that solutions to Pell’s equations correspond to units of \(\ints K\), so the goal of this section is to understand the structure of these units. These units form a multiplicative group \(\ints K^\times\) 33 so we’ll “embed” these in \(\R^2\) in a way that makes use of this multiplicative structure. Define

\[\begin{matrix} \ell: &\ints K^\times &\longrightarrow& \R^2\\ &u &\longmapsto& (\log|u|, \log|\conj u|)\\ \\ h: &(\R^\times)^2 &\longrightarrow& \R^2\\ &(x,y) &\longmapsto& (\log|x|, \log|y|) \end{matrix}\]Note that \(\ell=h\circ\iota\mid_{\ints K^\times}\). Furthermore, since \(N(u)=u\conj u=\pm1\) for any unit, \(\iota(\ints K^\times)\) lies on the hyperbola \(xy=\pm1\), since \(\log\)’s turn multiplication into addition 34 this means that \(\ell(\ints K^\times)\) lies on the line \(x+y=0\). The picure looks something like

Now, stare at \(\ell\) long enough for you to be convinced that \(\ker(\ell)=\{\pm1\}\). By the first isomorphism theorem, this means that

\[\begin{align*} \ell(\ints K^\times) \simeq \frac{\ints K^\times}{\{\pm1\}} \end{align*}\]Luckily for us, \(\ints K^\times\) is abelian 35 so we can write

\[\begin{align*} \zmod2\oplus\ell(\ints K^\times) \simeq \{\pm1\}\oplus\ell(\ints K^\times) \simeq \ints K^\times \end{align*}\]Thus, once we figure out what \(\ell(\ints K^\times)\) is, we will perfectly understand the structure of units in real quadratic fields. As it turn out, this group will be infinite cyclic, but we’ll first show it’s discrete. I’ve already been kind of loose with this, but just keep in mind that \(K\) is of the form \(\Q(\sqrt d)\) for some square free \(d\in\Z_{>1}\); I won’t always specify this.

Theorem

\(\ell(\ints K^\times)\) is discrete.

Now, remember earlier when I said that \(\ell(\ints K^\times)\) lies on the line \(x+y=0\)? Well, the previous theorem says this it is a discrete subgroup of this line. This line is a 1-dimensional real vector space, and there aren’t many discrete subgroups of such a space. In fact, there are two: \(\{0\}\) and \(\Z\). Thus, if we can show that \(\ell(\ints K^\times)\) has more than one element, then we will show this it must be \(\Z\) which will in turn show that Pell’s equations have infinitely many solutions. Even more than this, this will show that there exists an \(\eps\in\ints K^\times\) such that any unit has the form \(\pm\eps^n\) for some \(n\in\Z\), so all solutions to Pell’s equations are generated from a single solution! Getting ahead of myself because this is all still conjecture at this point, we will call such an \(\eps\) a fundamental unit of \(\ints K\).

The idea is to find to elements of \(\ints K\) that are equal in norm but not absolute value. Then, they must differ by a unit \(u\), and \(\ell(u)\neq0\) (why?), so there’s some nonzero elment which means the group must be \(\Z\), and we win.

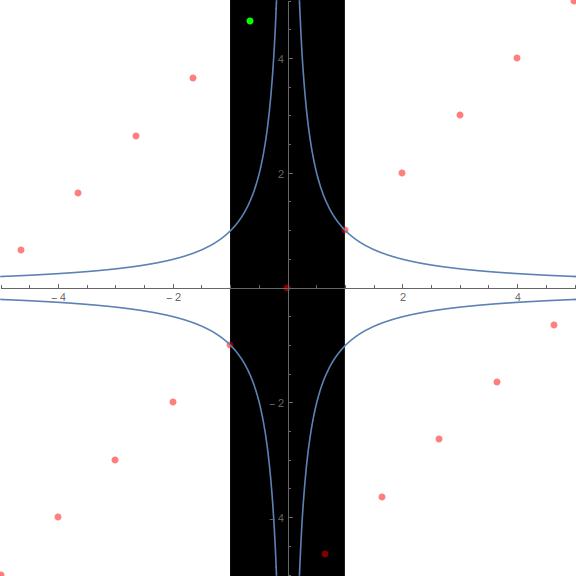

When writing the below proof, I got kinda lost in the details. To help me remember what everything is, and what’s going on, I quickly put together the following image. It’s not labelled or anything, but it illustrates the \(\alpha_\lambda\) (the x-coordinate of the green point) we are going to find, and why we can bound it’s absolute value both above and below.

Theorem

\(\ell(\ints K^\times)\simeq\Z\)

I should mention by appealing to absolute value, the above proof implicitly fixes a choice of an embedding \(K\hookrightarrow\R\). It doesn’t really matter which one is used, but worth noting what’s going on behind the scenes.

Pell at Last

Well, we’ve gone over a lot, and if you’re still here, kudos to you 36, but we’re finally ready to actually solve Pell’s equations. Fix any square free \(d\in\Z_{>1}\). Integer solutions to the equation \(x^2-dy^2=1\) are units of \(\ints{\Q(\sqrt d)}\), and these units are all in the form \(\pm\eps^n\) for some fundamental unit \(\eps\). In order to call this equation solved, we only need to find a fundamental unit. I’ll handle the case that \(d\equiv2,3\pmod4\). The other case can be done analagously, and figuring out its details is left as an exercise.

Assume \(d\equiv2,3\pmod4\) and \(\eps\) is a fundamental unit of \(K:=\Q(\sqrt d)\). Then, \(-\eps,\eps^{-1}\), and \(-\eps^{-1}\) are all fundamental units as well 37. Write \(\eps=a_1+b_1\sqrt d\) with \(a_1,b_1\in\Z^+\). We can always get positive coefficients by appropriately choosing one of the four fundamental units. Now let \(\eps^k:=a_k+b_k\sqrt d\) be the positive powers of \(\eps\) and note that \(b_k=a_1b_{k-1}+b_1a_{k-1}\) so the sequence \(\{b_k\}\) is increasing. Thus, if you want to find a fundamental unit, just guess and check. Start with \(b_1=1\) and check to see if \(db_1^2\pm1\) is a perfect square. If not, move on to \(b_1=2\) and repeat. Once you’ve found a value that works, write \(nb_1^2\pm1=a_1^2\) and your fundamental unit is \(a_1+b_1\sqrt d\).

Example

Let \(d=11\). If we take \(b_1=1\), then \(11b_1^2\pm1=\{10,12\}\) so no good. If we take \(b_1=2\), then \(11b_1^2\pm1=\{45,43\}\) so still no luck. Now we try \(b_1=3\) to get \(11b_1^2\pm1=\{100,98\}\) and we have a winner. Our fundamental unit is \(10+3\sqrt{11}\). Indeed, \(10^2-11*3^2=1\) is a solution to Pell’s equation.

Example

Now, take \(d=2\) instead. If we let \(b_1=1\), then \(2b_1^2\pm1=\{1,3\}\) so our fundamental unit is \(\eps=1+\sqrt 2\). However, this has norm \(1-2=-1\) so it’s not a solution to Pell’s equation. In cases like this, we instead focus our attention on \(\eps^2=3+2\sqrt2\) and use this to generate solutions.

I’d like to say that’s everything, but I’ve left a few loose ends. These include what to do if \(d\) isn’t square free, and what about the case where \(d\equiv1\pmod4\) so the fundamental unit can have non-integer coefficients. Honestly, I wanted to take care of them myself, but this post became much longer than I anticipated, so I’ll leave them to you. I will say that they have similar resolutions. The main issue in both cases is that \(\Z[\sqrt d]\) may not be all of \(\ints K\). However, it can be shown that in general, \(\Z[\sqrt d]\) has finite index in \(\ints K\). This means in particular that it is still infinite cyclic (why?), and so we still can find a fundamental unit \(\eps\in\Z[\sqrt d]^\times\). Then, solutions to Pell’s equation either correspond to powers of \(\eps\) or even powers of \(\eps\) depending on if \(\knorm(\eps)=\pm1\).

-

Just finished day one of writing this, and it looks like this will end up being my longest post yet by a sizeable amount. I could be wrong about the sizeable amount part (hard to tell), but either way, this post is gonna dethrone the king… Having just now finished writing this thing, something tells me it will hold the title of longest post for quite some time. In case anyone’s curious, the previous record holder had a little under 26,650 characters. This one has around 45,000. ↩

-

I usually try not to have prereqs for gaining understanding from my posts, but for this one, I feel like you should at least be comfortable with linear algebra (and in particular abstract vector spaces and determinants), or you’ll likely be lost at some key points. Once we start talking about embeddings, a little bit of abstract algebra will help too (in particular, knowing about group homomorphisms) ↩

-

this statement can be made precise and proven. I might do that if ever I come up with a good excuse to introduce computability theory on this blog. ↩

-

another way to do it is hinted at at the beginning of the second half of that post. You just need to use the fact that the norm N(a+bi)=a^2+b^2 of a Guassian integer is multiplicative. ↩

-

because I forgot it was possible for it not to be the case (i.e. I forgot square numbers exist) ↩

-

I should mention that, as is not uncommon in this blog, this post won’t necessarily present the simplest way to solve things, but instead opt for one that introduces interesting mathematics. Also, as always, minimal planning is done before I begin writing so almost certainly details will be missing or presented out of their usual order. It is up to the reader to reconstruct coherent arguments where this happens (it’s a good test of understanding) ↩

-

from infinite to finite ↩

-

some people will try to tell you that this is impossible, but do not be fooled. I believe in you, and I know you can let out a gasp if you so will it. ↩

-

at this point, you might wonder why I didn’t just write the problem like this in the first place. That’s because the place I stole it from wrote it as y^2=x^3-2 originally as well. ↩

-

if you don’t know what this is, it basically means that the fundamental theorem of arithmetic holds: every integer can be factored uniquely into primes ↩

-

For example, let d^2=-5. Then, Z[d] is not a UFD since 2*3=(1+d)(1-d) and all of these are (different) primes ↩

-

Not a technical term. What I mean is that if you have x,y in Z[-sqrt{2}], then x/y exists in Q(-sqrt{2}), and this is what I mean by their ambient quotient. ↩

-

If you write it as the product of two numbers, one of them is a unit ↩

-

I’m gonna use some algrebraic words like field, ring, etc. in this section. If you don’t know what they are, that’s fine; I don’t think knowing their definition is technically required to understand how we’re gonna solve Pell’s equations. I’ll also try to include watered-down versions of what they mean for some of them. For example, a ring is a set with addition and multiplication. A field, has both of these plus division. Integers are a ring; fractions are a field. ↩

-

A field extension K of Q (often written K/Q) is just a field K that contains Q (Ex. R is a field extension of Q). Every field extension has a degree d (written [K:Q]) which is a measure of much bigger K is than Q (formally speaking, if K/Q is a field extension, then K is a Q-vector space (why?) and the degree of K/Q is the Q-dimension of K as a vector space). We say a field extension is finite if it has finite degree (ex. Q(sqrt{-2}) is a finite field extension of Q (of degree 2) and hence a number field. R is and infinite field extension of Q and hence not a number field) ↩

-

Monic just means the leading coefficient is 1. The set Z[X] is just the set of polynomials with integer coefficients. An example of an algebraic integer is sqrt{-2} because it satisfied X^2 + 2 = 0 ↩

-

That O is \mathscr and not \mathcal. This is important. ↩

-

Hence the name quadratic ↩

-

This is no coincidence, but we won’t get into the reason why here. ↩

-

It’s true in general, but the general proof requires a property of the norm I won’t mention here since the norm isn’t always given as a nice product. We got lucky here that quadratic fields are in a sense “complete” (read: Galois) ↩

-

In general, if L/K is an extension of number fields, then N_{L/K}(O_L) is a subset of O_K. In other words, the norm always maps algebraic integers into algebraic integers. ↩

-

Although maybe you’ve already made the connection by now ↩

-

If I’m wrong, we’ll introduce the other stuff as it pops up ↩

-

Which reminds me, why don’t we consider the case d = 0 (mod 4) in the previous theorem? ↩

-

Why not just call this dimension? Because lattices are free Z-modules, and free modules have rank instead of dimesnion. Modules are something I want to talk about on this blog at some point, but for now, just know that although lattices have geometric interpretations, modules (and even free modules) in general do not (unlike typical vector spaces), so we use the less geometric-sounding rank instead of dimension. ↩

-

for our purposes, the plus in a circle is just another way of writing the direct product. It has the advantage of looking like addition which is good because the dimension of A x B is dim A + dim B instead of dim A * dim B. This notation helps hint at the idea that things should be thought of additively, so you might want to represent the pair (a,b) in A x B as a single value a+b instead (be warned. This is not always a legitimate alternate representation of pairs) ↩

-

By numbers, I mean as in number theory. i.e. integers and their analouges ↩

-

parrallelopiped? ↩

-

meaning it contains all the points on its boundary ↩

-

i.e. a function f that preserves addition and multiplication in the sense that f(ab)=f(a)f(b) and f(a+b)=f(a)+f(b) ↩

-

there’s some abuse of notation going on here. In a number field, sqrt(d) is really just an abstract number whose square happens to be d whereas in the setting of real numbers (where there are two numbers matching this description) it is specifically the positive sqrt(d). ↩

-

as far as I know, there isn’t some deep reason why this expression in particular works. It’s just a happy coincidence. I could be wrong though; coincidences are rare in math. ↩

-

this basically just means if you multiply two units you get another unit, but the same doesn’t necessarily hold for addition ↩

-

and since log(1)=0 ↩

-

plus possibly an argument involving splitting O_K^x into “positive” and “negative” parts and mentioning phrases like semidirect product (the argument I have in my head does this, but I’m pretty sure it’s overkill)… A different argument is to notice that O_K^x is an extension of {+/-1} and l(O_K^x). Hence, we get this conslusion by noticing letting N: O_K^x -> {+/-1} be the norm, the map a |-> N(a)*sign(a) is a splitting map. ↩

-

no way I’d ever read this much math without losing interest and moving on to something else ↩

-

if you fix an embedding into R, then the unique fundamental unit > 1 is often called the fundamental unit ↩